Editor’s note — Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has, rightly, monopolized the thoughts and attention of most people in the world. I’m no exception. I’m deeply unqualified to opine on the conflict itself, but I did want to use the newsletter to point you to a couple of places you can help. UNICEF is raising money to protect children in Ukraine. And, if you have some spare cryptocurrency, the government of Ukraine is encouraging donations in BTC, ETH, and USDT. 🇺🇦

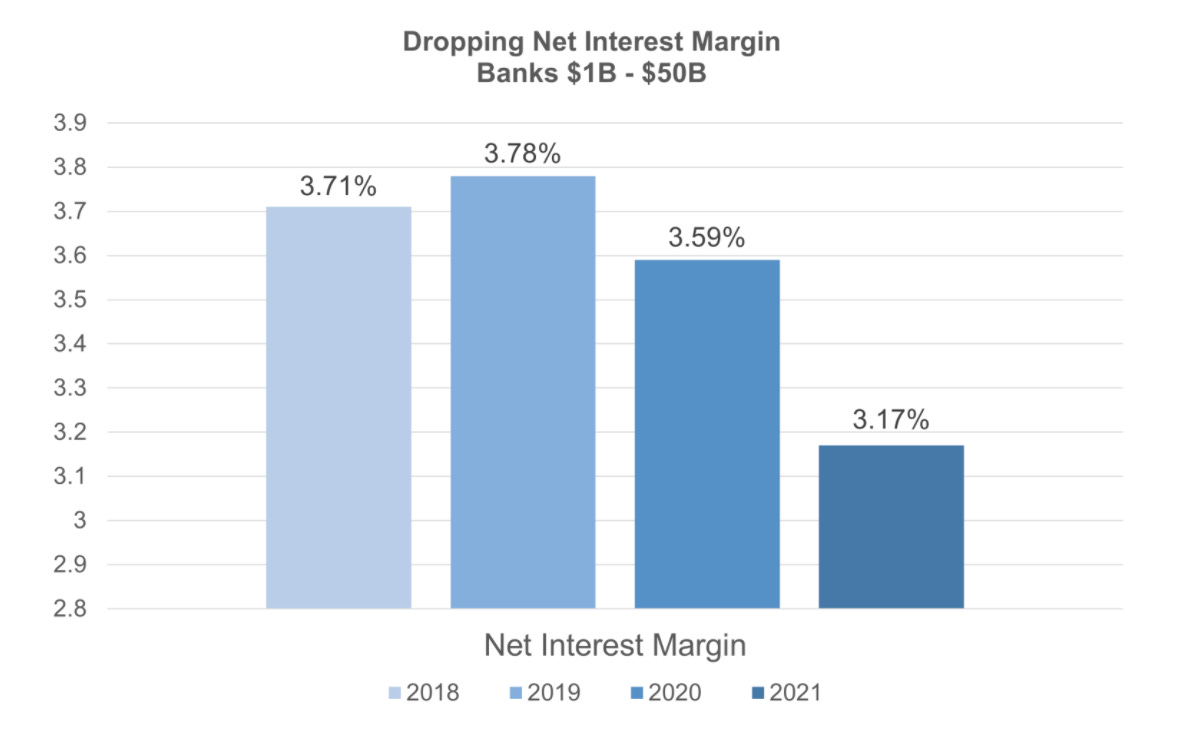

This is what the last four years have looked like for mid-size banks in the U.S.:

Not ideal, especially when you consider that interest income makes up roughly 75% of these banks’ total revenue and that the remaining 25% (non-interest income) is very likely to decrease in the coming years as overdraft fee revenue disappears and payments fee revenue continues to shift towards bigger banks and non-bank competitors.

This is what the last four years have looked like for private fintech companies1:

To put this in a broader context, venture investing in fintech has grown to the point where one in every five venture capital dollars invested last year was invested in a fintech company.

So, to sum up, mid-size banks are facing a revenue recession that seems likely to sustain for at least the next couple of years and fintech companies are benefiting from an outrageously bullish private market that shows no signs of slowing down.

In most industries, this would be the end of the story; incumbents struggle as disruptors (funded by investors that smell blood in the water) proliferate.

However, financial services isn’t, as we know, like most other industries.

U.S. banks, despite their struggles, have something that any aspiring fintech competitor needs — a bank charter.

So let’s back up and re-sum up the situation — it’s become harder for mid-size banks to make money in the ways they traditionally have, but they have an asset that many U.S. fintech companies, which raised $18.2 billion in just the last quarter of 2021, need in order to do business.

You smell that? What is that?

In a recent research report, Cornerstone Advisors defined banking as a service (BaaS) as:

A strategy where a financial institution partners with a fintech or other non-financial institution (i.e., brands) to provide financial services to the partner’s customer base, leveraging the financial institution’s charter and capabilities like account management, compliance, fraud management, and payment and/or lending services.

Put more simply, it’s an incredibly cost effective distribution strategy, as illustrated by the return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) achieved by the 30 or so U.S. banks currently dominating the BaaS space:

These profitability metrics help explain why, in a survey of financial institutions by Cornerstone Advisors, 11% of banks reported that they are pursuing a BaaS strategy, 8% are in the process of developing a BaaS strategy, and 20% are considering pursuing a BaaS strategy.

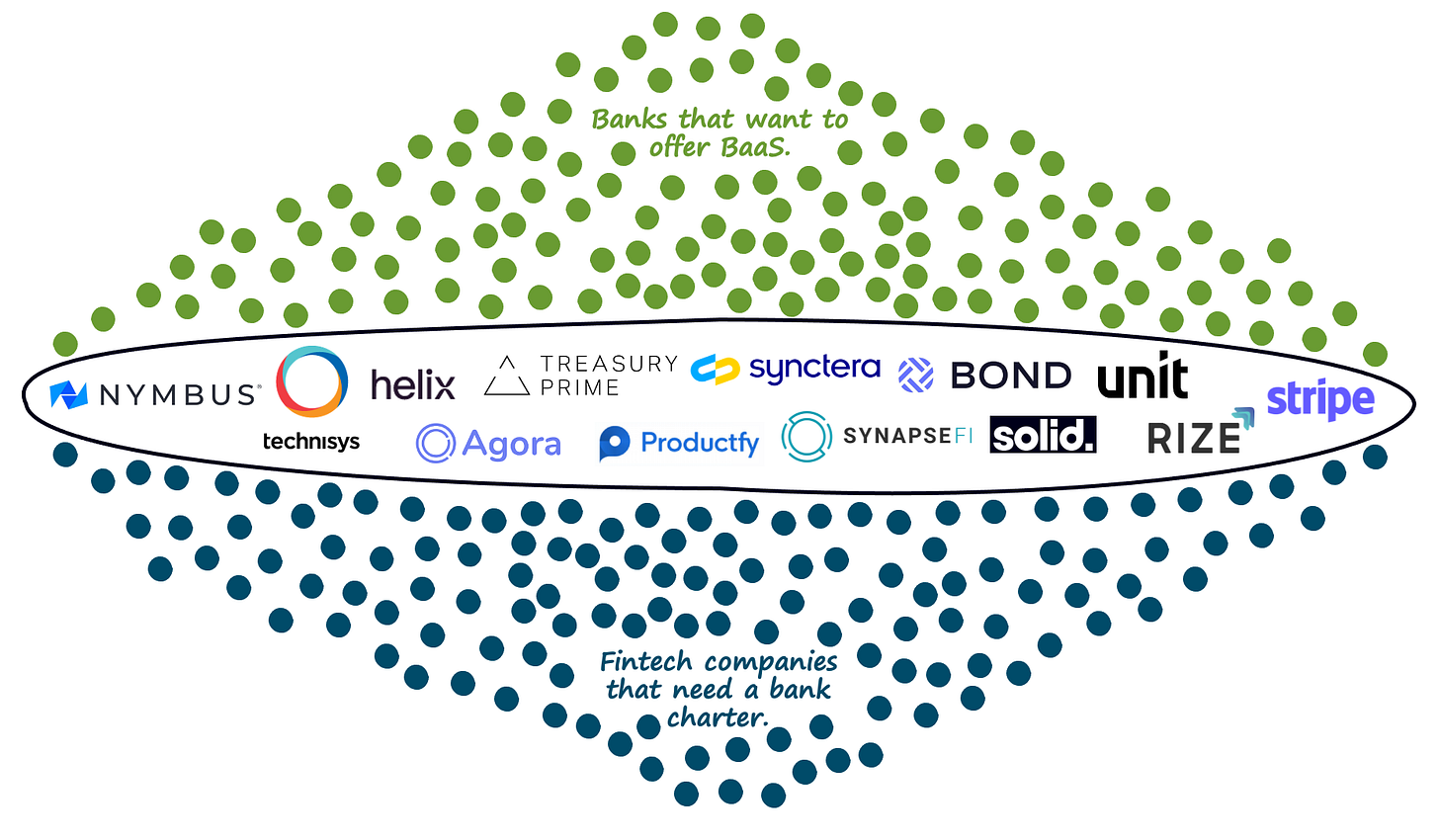

It also explains the emergence of BaaS platforms, which provide the technical, operational, and legal middleware between banks wanting to offer BaaS and fintech companies that need to find and integrate a bank partner (or partners).

For fintech companies, these platforms match them up with the bank partners that will best fit their vision and reduce their time to market and upfront and ongoing expenses by orders of magnitude.

For banks, these platforms match them up with the fintech companies that best fit their target risk/return profile and significantly streamline the process of evaluating, onboarding, and supporting those fintech partners.

In exchange for these benefits, BaaS platforms take a cut of the revenue generated by the partnerships they facilitate, which comes from a number of different sources including interchange, ACH, KYC/KYB, fraud management, remote deposit capture, and card processing.

BaaS Today

So, to sum up where we are today, we have:

Supply: Ongoing margin compression, decreasing non-interest income, and an increasingly competitive customer acquisition environment means that we should have a growing supply of mid-size banks looking to offer BaaS.

Demand: The amount of money pouring into fintech, particularly in the form of larger pre-seed, seed, and Series A rounds, gives us a healthy demand for bank partners for the foreseeable future.

Market Makers: Growth in both supply and demand combined with the technical, operational, and legal challenges of BaaS, has led to the creation of BaaS platforms, which exist to make partnering easier for everyone.

All of which tees up an even more important question — where will we be tomorrow?

BaaS Tomorrow

The short answer is I have absolutely no idea!

(helpful, I know)

The slightly longer answer is that while I can’t predict the exact future of banking as a service in the U.S., I do have a few questions that are starting to shape my thinking on this subject.

#1: How many banks does BaaS need? And how do banks differentiate themselves when BaaS gets more crowded?

According to projections from Cornerstone Advisors, the U.S. banking as a service market could grow from approximately $1.2 billion in revenue in 2021 to more than $25 billion by 2026. This projection is based on an assumption that the total number of banks offering BaaS services increases tenfold (to roughly 300) during that period, which seems entirely reasonable given the incentives for mid-size banks to participate in BaaS that I laid out above.

My question is where, in that growth curve, might we start to see diminishing returns for banks?

Banks’ fear of BaaS has always been that it will disintermediate them from the end customer and relegate them to being ‘dumb pipes’. For the most part, this concern strikes me as misguided. Fintech is already disintermediating banks from their customers and if BaaS can offer these banks a revenue lifeline, they should take it!

That said, it seems likely that at some point the sheer number of banks participating in BaaS will make it difficult for any one bank to significantly differentiate its offerings, which is a classic recipe for commoditization and margin compression. What will banks do then?

#2: Will big banks break into BaaS?

The conventional wisdom in BaaS is that the banks best suited to partnering with fintech companies are mid-size and community institutions under $10 billion in assets. Such banks are able to offer their partners a more generous split on debit interchange revenue (because there’s more of it to go around thanks to the Durbin Amendment).

While this explains why BaaS has evolved the way that it has, it by no means guarantees that it will remain true moving forward. Banks with more than $10 billion in assets could easily compete for fintech partnerships by offering a more generous debit interchange split (off of a smaller total) or by specializing in areas outside of debit cards (which is already a very crowded category in neobank land). For example, I’d be fascinated to see a super-regional bank with strong consumer lending expertise (and a large balance sheet) build a BaaS offering focused on enabling lending-first fintech companies looking for more support than a community bank or community bank + BaaS platform can offer.

#3: Will fintech demand for BaaS remain as inexhaustible as it seems right now?

I know I made a whole case for the demand side of the BaaS equation above, but what if I’m wrong?

Fintech companies that went public in 2021 have been taking an absolute beating in the public markets, as Alex Wilhelm at TechCrunch noted recently:

Nu, the parent company of Nubank, reported its fourth-quarter financial performance, and in response to rapid revenue growth and improving economics, the company saw its value drop 9% in regular trading today after falling sharply in recent sessions. Now worth just $8 per share, Nu is underwater from its IPO price and down about a third from its all-time highs.

BNPL leader Affirm has seen its value crater from $176.65 at its peak to just $36.24 today. Robinhood has seen its value fall from a high of $85 per share to $11.28 this morning. SoFi has taken lumps as well, suffering declines from a 52-week crest of $24.95 per share to just $10.10 today.

These results are starting to ripple backwards into the private market. Forbes recently reported that Chime, which was originally planning an IPO for early this year may be planning to delay that entrance into the public market until late 2022. Other late-stage private fintech companies will likely exercise patience as well.

The big question — will this ripple impact the ability for early-stage fintech companies to raise money? Will it be as easy to fundraise for YAN (yet another neobank) a year from now as it was a year ago? And if not, how will that impact the demand-side of the BaaS market?

Oh, and on a related note:

#4: How will fintech companies getting bank charters impact BaaS?

There aren’t a lot of examples of fintech companies actually getting bank charters — Varo, LendingClub, Block, and SoFi are the only ones I can think of — but I wonder if these companies’ successes plus a shift in focus away from growth to profitability for fintech companies (due to shifting public market sentiments) might motivate fintech companies to pull the trigger on a charter (and all the expense and pain that entails) a little earlier in their journeys than they might have before.

And if that becomes more common (especially if regulators streamline that path a bit more) how will that impact demand for BaaS for both banks and BaaS platforms?

#5: Will fraud and compliance issues scare banks off of BaaS?

I thought this blog post from early January, announcing changes to LendingClub’s business, was pretty interesting (emphasis mine):

LendingClub completed the acquisition of Radius Bank in February 2021. At that time, in addition to the direct-to-consumer deposit business, we inherited a fintech partner program, and several lending businesses. As we reach the one-year anniversary of the acquisition, and in conjunction with the conclusion of a strategic review of our business operations, we have made the decision to discontinue certain businesses that don’t fit our mission.

During the review, we also thoroughly examined relationships and operating activities for the fintech partners. As a result of our review, we are asking certain partners to modify their activities and/or operations to match expectations and contractual commitments, and we have begun exiting certain partners. As part of the ongoing dialogue with these partners, we have discussed transition plans or operational changes that could impact the services available to these partners and their customers.

What “activities and/or operations” from fintech partners might have been concerning to LendingClub? Maybe an excessive amount of fraud? Here’s an excerpt from a Forbes article published just a few weeks before the LendingClub announcement (emphasis mine, again):

Forbes has learned that Robinhood, the dominant free stock trading app with 22 million active users, has become the latest fintech to ban transfers from a specific list of institutions as a blunt tool for fighting fraud.

Robinhood declined to disclose the specific institutions on the list, but Forbes has learned that it contains a wide variety of banks, including a heavy concentration of neobanks and the moderate-sized banks they partner with, plus a small number of large, traditional brick-and-mortar institutions. Some of the names on the list include: LendingClub; Ohio-based Sutton Bank (one of the partner banks that Square’s Cash App uses to store customer deposits); Tennessee-based First Century Bank (one of the partner banks for PayPal’s Cash Card); prepaid card issuer and digital bank Green Dot; New York-based Metropolitan Commercial Bank (the partner bank for digital bank Current); and Iowa-based Lincoln Savings Bank (one of the partner banks for fintech apps such as Cash App and Acorns).

Banks offering BaaS services to fintech companies generally aren’t liable for transaction fraud losses, but that doesn’t mean that excessive amounts of fraud can’t negatively impact those banks’ reputations, both at a network level and in the minds of regulators.

Will this growing vector of risks scare banks off of BaaS?

#6: Which BaaS platform bet will prove wiser?

There’s a lot of nuance in the BaaS platform space, but at a high level most BaaS platform companies are following one of two different playbooks. For our purposes, we’ll refer to them as the AWS playbook and the Hinge playbook.

First, the AWS playbook. Companies like Bond, Unit, and Rize are building developer-first platforms that focus on abstracting away as much complexity from the process of launching a financial product as possible. The goal is to make it drop-dead simple, just like spinning up a computing environment with AWS. No need to think about the bank partner on the other end. No need to worry about compliance.

This model can work for fintech companies, but it’s really designed for non-finance companies (SaaS companies, in particular) that are interested in embedding financial products into their core products/apps/experiences. Think Lyft offering a debit card for its drivers. Unlike fintech companies, which need to make the majority of their revenue from the financial products they offer and are thus very motivated to care about the details of bank partnerships and revenue splits, non-finance brands like Lyft make their money outside financial services. These brands want to add banking to make their products stickier, improve customer satisfaction, and diversify their revenue streams. There is a high likelihood that they will never want to take more ownership of the stack underpinning their financial product(s). It just needs to work. For bank partners, the benefit of this model is a turnkey BaaS channel that can be activated quickly and can start generating revenue with little upfront or ongoing work.

The Hinge playbook is, essentially, the opposite. The name is in reference to the Hinge dating app, which markets itself as “the dating app designed to be deleted”.2 Companies like Synctera and Treasury Prime that are pursuing this model are building platforms that focus on matching up fintech companies and banks in mutually beneficial partnerships. Rather than abstracting the partner banks out of the equation entirely, these platforms focus on helping fintech companies find partner banks that they will love:

These platforms streamline the process of creating and launching financial products (just like the AWS model), but never at the expense of keeping their fintech and bank clients in control. This model is a better fit for fintech companies, which are naturally incentivized to care about the compliance and unit economics of their products at a level of detail that non-finance companies usually aren’t. It’s also a better fit for larger and more sophisticated partner banks that have the resources and in-house expertise to work directly with fintech founders and want more ownership over compliance and risk management in BaaS. The Hinge model, like the dating app it’s named after, comes with the possibility of more long-term attrition, which can be offset by being the model of choice for new customers coming on.

Which model — AWS or Hinge — will prove to be more successful over time? I don’t know. It depends on how bullish you are about the future of embedded finance and how pessimistic you are that banks and fintech companies will ever be able to find love without matchmaking.

#7: Will BaaS platforms eat the core banking market?

Imagine this hypothetical — traditional banks turn, in increasing numbers, to BaaS platforms in order to start generating new revenue. They utilize these platforms’ built-in banking functionality (ledgers, processing, account management, etc.) rather than trying to integrate with their own, which would take too much time and money. As the BaaS platforms prove themselves and BaaS revenues bolster these banks’ bottom lines, the banks eventually port their customer-facing portfolios over to these platforms as well. At the same time, fintech companies operating on these platforms continue to scale up. Even as they grow and potentially acquire their own charters, they continue to utilize the BaaS platforms’ functionality. One day, we all look up and realize that the legacy core banking providers (FIS, Fiserv, Jack Henry, etc.) have been effectively supplanted by a new generation of competitors that started out in BaaS (Nymbus, Agora, Technisys, etc.)

Plausible?

#8: Will BaaS become the new strategic pivot for neobanks?

A popular move, in the first few generations of fintech, was the B2C-to-B2B pivot. Companies that started in B2C and built all the technology necessary to directly serve consumers or small businesses (Moven, Avant, Petal) realized that the technology they built could be spun off and sold to their competitors (Moven Enterprise, Amount, Prism Data) and sometimes that B2B play ended up being the easier and/or more lucrative approach.

I wonder if this current generation of fintech companies is quietly perfecting the next great strategic pivot — the B2C-to-BaaS pivot.

The basic formula would look something like this — start a B2C neobank, build and/or buy the technology stack necessary to operate the neobank with few external dependencies, acquire a bank charter, and pivot.

In related news:

And also:

Jiko, the fintech startup that made headlines last year when it gained a national charter after purchasing a small Minnesota-based community bank, said it is pivoting from its consumer-focused model and accelerating its business-to-business strategy.

"We always had this idea that at some point we would open up the [application programming interfaces]. We knew from the beginning that it wouldn't just be for the app," said Jiko co-founder and CEO Stephane Lintner, adding banking-as-a-service (BaaS) was a vision the startup had "early in its DNA."

#9: What’s the next “whoa, that came out of nowhere” BaaS platform play?

I have to admit, I didn’t see the SoFi acquisition of Technisys coming. But that’s the neat thing about BaaS. It sits at the intersection of so many different trends in financial services and fintech that it is constantly surprising.

So, what’s the next surprise going to be?

Here are a couple of wild, out-of-left-field guesses:

A VC firm creates or buys a BaaS platform. A key challenge for BaaS platforms is ensuring that they have adequate demand (companies looking to work with bank partners to launch banking products). A key challenge for fintech VC firms is offering value-added services (i.e. stuff besides money) to fintech founders that ensure that the VC firm gets into the deals that it wants. This seems like a win-win, no?

Big tech gets into the BaaS platform business. If you believe that eventually every SaaS company will embed financial services and become a fintech company, then wouldn’t it be logical to assume that the biggest and most powerful service providers for SaaS companies might eventually build BaaS platforms to help facilitate that transition? Hell, Stripe already has with its Treasury product (which powers Shopify Balance). I could see AWS jumping in. I could especially see Google adding BaaS in alongside Google Cloud as part of its renewed push to sell to (rather than compete with) banks.

Visa and Mastercard add BaaS services. The card networks’ superpower isn’t payments or commerce enablement. It’s maintaining balance in a multisided network where the network participants don’t like each other very much. If BaaS grows into an opportunity that interests banks above $10 billion in assets and embedded finance really takes off, I could see Visa and Mastercard adding BaaS services that connect the two sides of their networks together in an entirely new way.

Regulators create a public-sector BaaS platform alternative. To preface this, there’s absolutely no way that this happens. But, imagine this — the OCC builds a federal fintech sandbox that comes with the option for fintech companies to use their built-in BaaS platform. The platform is low-cost for the fintech company because the government doesn’t take a cut, but rather passes the modest amount of revenue from the revenue split to the participating banks. The banks get the revenue plus a headache-free compliance set up. Regulators get front-row seats to fintech companies’ operations and policies (and banks’ BaaS operations). And fintech companies (in addition to a low-cost BaaS platform) get a streamlined path to a bank charter in the future.

DeFi Mullets-as-a-Service (DFMaaS) becomes a thing. Companies like Eco and OnJuno are creating neobanks on top of crypto infrastructure (DeFi mullet = fintech in the front, crypto in the back). If they are successful, could they inspire the creation of BaaS-like platforms focused on making it easier and quicker to build and launch similar products? The open question here would be what role (if any) would banks play?

Short Takes

1.) Little sizzle for Sezzle.

BNPL provider Zip is buying fellow BNPL provider Sezzle for $354 million in an all-stock deal.

Short take: As Alex Wilhelm at TechCrunch observed, this price values Sezzle’s projected annual revenue at a surprisingly low 2.7x multiple (by contrast, Affirm’s valuation, even after a rough stretch in the public markets, is 8x its current revenue). This suggests that the manic enthusiasm driving private BNPL companies’ valuations may finally be tailing off.

2.) Faster payments for produce growers.

Farm lending platform ProducePay announced Quick-Pay+, a service to get growers 96% of the price of a shipment in 24 hours.

Short take: Financing for produce growers with no requirement that borrowers use land as collateral or repay the loan before products go to market? Provided by a company that was founded by a fourth-generation Mexican farmer? This is exactly why I love fintech. More of this please!

3.) Citi comes over from the dark side.

Citi announced plans to eliminate overdraft fees, returned item fees and overdraft protection fees this summer.

Short take: Good news: this puts more pressure on banks that haven’t made moves on overdraft yet. Bad news: among the big four banks, Citi is by far the least dependent on overdraft fee revenue. Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and Wells Fargo have made smaller moves on overdraft, but no one should be satisfied yet.

Research Corner

The BaaS research from Cornerstone Advisors that I referenced multiple times in this piece comes from a recently released report (commissioned by Synctera) — Banking as a Service: Banks’ $25 Billion Revenue Opportunity in Fintech Banking.

The report goes deep into the opportunity for banks to participate in the growing BaaS market and provides practical advice for banks on evaluating BaaS platforms and fintech partners.

You can download the report, for free, here.

Alex Johnson is a Director of Fintech Research at Cornerstone Advisors, where he publishes commissioned research reports on fintech trends and advises both established and startup financial technology companies.

Twitter: @AlexH_Johnson

LinkedIn: Linkedin.com/in/alexhjohnson/

These numbers are global, but the trend looks similar if you narrow in on the U.S. (which has been the hottest fintech market during this span).

Since you asked (OK … you didn’t ask, but I could tell you were curious), here are three interesting things about Hinge: 1.) The company nearly ran out of money when the founder spent lavishly on a launch party in Washington DC. 2.) Hinge’s focus on long-term compatibility worked, it received more mentions than any other dating app in the Weddings section of The New York Times in 2017. 3.) After making an initial investment in 2017, Match Group (which owns 45 different online dating services including Tinder, Match.com, and OkCupid) acquired Hinge in 2019.