How is Fintech Impacting Financial Services?

To answer this question, study the banks that have the most to win (or lose).

What’s the best way to understand the impact of fintech on the U.S. financial services industry?

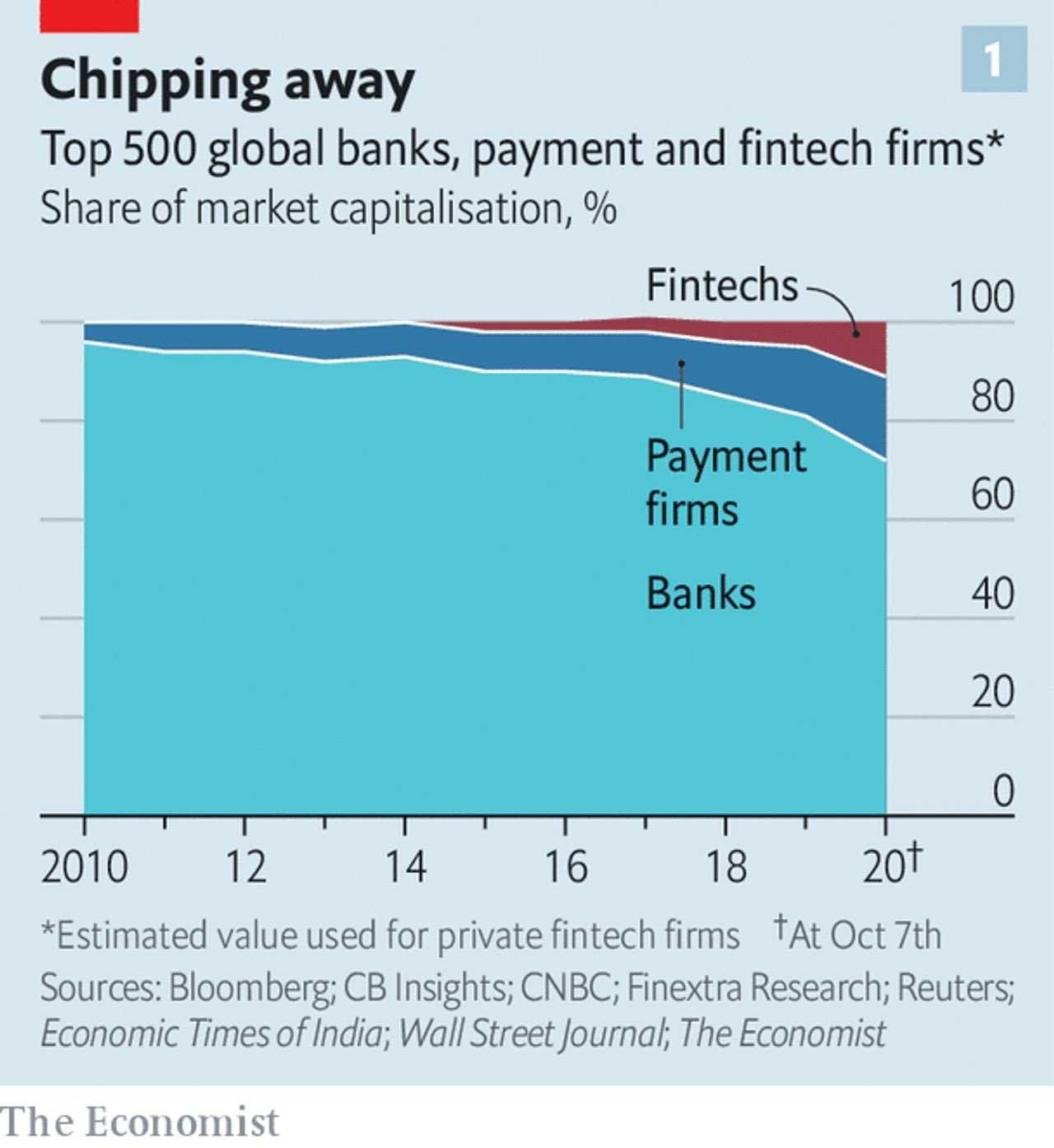

At a macro level, you can look at things like share of market capitalization in financial services:

And as Simon Taylor at 11:FS persuasively argues, these types of graphics are a pretty good leading indicator of the impact fintech is having and will continue to have:

I get it; the P/E multiples right now are more than a little frothy (especially when you consider Tesla has a P/E multiple of nearly 1,100x). But zoom out. Either we're living through a form of the industrial revolution, as the economy shifts to digital or we're not. This is why tech always looks overpriced on a 12-month time horizon, but probably fairly (or under) priced in 10 years. People often point out payment firms don't always compete with banks, and the market cap isn't a fair measure of market impact or earnings.

But you can't ignore the fact that Square is nearly as big as Goldman, and PayPal close to JP Morgan's market cap.

However, I think these macro statistics miss important nuances. If you want to understand the impact that fintech is having, especially in the immediate term, you also need to study the micro level — the strategic choices that specific banks are being forced to make in response to the pressure being exerted by fintech competitors.

The question is which bank do you study?

The Goldilocks Theory

Let’s run down the list:

National banks. The problem with these banks is that they’re too big. They can afford to stick with ill-conceived strategies (more branches, really?) for a long time and they have the technology chops and budgets to catch up on digital quickly when they finally decide to pivot (like the kid in high school who doesn’t pick up a basketball all summer and then breezes through tryouts).

Community banks. It’s going to be tough sledding for these companies, regardless of what they do. Locked into rigid core banking platforms and operating with minimal IT resources, their options are extremely limited. Many of these banks are going to be acquired or will pivot to Banking-as-a-Service (which can be a highly profitable option, as Rex Salisbury at Andreessen Horowitz points out).

Regional banks. This is the sweet spot. Not so small that they can’t (in theory) catch up and start delivering customer experiences comparable to the national banks and fintech companies. Not so big that they can keep making strategic mistakes and survive.

I’m obsessed with large regional U.S. banks. These are the companies that have the most to gain (or lose) by making (or not making) the right decisions in response to the growth of fintech. Their strategic priorities tell us, better than anything, where fintech is truly having an impact.

The $12 Billion Financial Services Company You Never Think About

Chime, the most valuable private B2C fintech company in the U.S., has a market cap of $14.5 billion. Robinhood is number two at $11.2 billion.

Pop quiz — which U.S. bank fits squarely between Chime and Robinhood with a market cap of $12.5 billion?

That would be the 195 year-old KeyBank, based out of Cleveland, Ohio.

KeyBank serves retail and commercial banking customers in 15 states. It operates 1,077 branches across the U.S. (predominantly in the midwest). It employees nearly 18,000 people.

And it just reported its Q3 earnings, which provides a fascinating window into the strategic direction of the 29th largest bank in the U.S.

How is KeyBank Navigating Disruption?

Let’s run through three fintech megatrends, see how KeyBank is responding to them, and suss out what those responses might mean for the future of the industry at large.

Megatrend #1: Digital channels are displacing branches.

In response, KeyBank is: rationalizing its branch footprint. Here’s KeyBank’s CEO, Chris Gorman:

We think the pandemic certainly accelerated some trends that were already there. Just to give you some texture. When we bought First Niagara, we had 1,600 branches.

Today, we have 1,077. We've invested heavily in digital. Our digital take up, more than 60% of our customers are now digitally active. And so we actually think there is a significant opportunity to take a look at the fleet.

And we're in the final throes of planning that, and we'll have more to say on that in January. But in addition to some other things that are fundamental changes, we do think there'll be a change in kind of how we look at the density of our branches. And as you know, we're in some fast-growing areas where we have relatively thin branch footprints, and we think we can replicate that and get the mix right of digital and physical in other parts of our franchise.

KeyBank still clearly believes in the importance of a physical presence in fast-growing markets, but the design and purpose of those physical locations appears to be changing:

Key recently announced that it will open its first newly constructed tellerless branch on May 13 in Boulder, Colo. It'll be the first tellerless branch opened that was specifically built for that model.

An existing branch in the city will relocate to the new one, which instead of teller lines features private offices where interactions with bankers trained as "financial wellness consultants."

What this means: KeyBank has 1,077 branches and 18,000 employees. Chime has 0 branches and less than 1,000 employees. That differential in cost structure is not a winning competitive formula for KeyBank, even in a post-pandemic environment.

That said, the anti-branch fervor in fintech obscures a fundamental truth — some consumers do value going into a branch for some things. According to the FDIC, between 2017 and 2019, the percentage of households that used mobile as the primary method to access their bank account jumped from 15.6% to 34%. Not surprising. What is surprising is that this jump in mobile came not at the expense of the branch (which saw a modest drop from 24.3% in 2017 to 21% in 2019) but rather from online, which dropped from 36% in 2017 to 22.8% in 2019.

Maybe the pandemic permanently alters the preferences of that last 21% of consumers who were primarily using the branch in 2019. Or maybe not.

In response, KeyBank is: focusing on “relationship products”. Here’s Chris Gorman explaining why KeyBank has decided to exit the indirect auto lending business, where it currently has a $4.6 billion portfolio:

we've talked a lot about relationships. We've talked a lot about targeted scale. And frankly, the indirect book was, from a quality perspective, it's just fine.

From a return perspective, obviously, you can't generate the kind of relationship returns that we would expect because it's a single product.

KeyBank believes this focus on relationship products, such as retail mortgage, has (and will continue to) position them for success, even in tough lending environments:

Key really has pivoted to a relationship strategy. And if you take a look at where the portfolio was before the last crisis, that it was more transaction-oriented as opposed to relationship. … after the financial crisis, we sat down and evaluated where we lost money, how we lost money? … It was where we didn't have a deep relationship. In some cases, it was a business that was indirect business, third-party business. And we went about the business of derisking our portfolio. And we have been disciplined enough that we have foregone revenues such that we could position ourselves.

What this means: It’s easy to forget, but banks do a lot of stuff that falls way outside of traditional, relationship-based retail banking. KeyBank’s old CEO, Robert Gillespie, was famous for wheeling and dealing KeyBank into all kinds of ancillary markets during his tenure, everything from investment banking to equipment financing.

With B2C fintech companies aggressively trying to peal off banks’ core customers and cross-sell additional products to them (see SoFi for a recent example), I expect other banks to take a hard look at the transactional parts of their business that don’t strengthen the overall relationships they have with their target customers.

Megatrend #3: Lending is being digitized and embedded in order to better serve niche customer segments.

In response, KeyBank is: doubling down on their 2019 acquisition of Laurel Road, a digital lender focused on debt consolidation loans. Here’s Chris Gorman describing KeyBank’s vision for leveraging Laurel Road’s technology to build a digital bank for healthcare professionals:

So this is something that we're, frankly, very excited about. We're building a national digital bank, and it's going to be focused on healthcare professionals.

That's all digital. Then in many cases, within six months something like 50% of those customers that refinance their doctor or dentist loans -- dental school loans, buy a home. We've now built a complete digital mortgage application. And where we can take it from there is, on a national basis, to be really focused around doctors and dentists in terms of opening accounts, etc.

And that will open up the opportunity for us, in the case of dentists most because they're mostly independent business people as opposed to doctors who are part of large groups. That will give us an avenue to do a lot with them. So we see Laurel Road as a platform that we've grown a lot. It's been -- it's achieved everything we hoped it would, and we think there's a lot to do on top of it.

What this means: Banks are waking up to the idea that there is a layer of value above the products that they currently offer. This is the driving force behind the development of a lot of new neobanks. Simon Taylor puts it best:

From above, Neobanks and non-bank brands are adding more value as they get closer to the customer problem or serve segments the banks can't.

A bank for couples. A bank for new parents. A bank for landlords.

A bank for healthcare professionals is, IMO, still a little too broad of a customer segment, but KeyBank has the right idea. Expect other banks to follow suit.

Short Takes

(Sourced from This Week in Fintech)

A Reward for Good Behavior

Neobank Upgrade added 1.5% cash back rewards to its credit card, when customers make their monthly payments.

Short take: Between Upgrade and SoFi, which recently introduced unlimited 2% cash back when rewards are put towards paying down debt or saving, it’s clear that neobanks are using credit card rewards to incentivize financially healthy behavior. This has the double benefit of helping customers and reducing risk (or driving revenue in SoFi’s case) for the companies. Smart.

Under Pressure

Early wage access startups like DailyPay, PayActiv, Dave, and Earnin have experienced significant growth due to the economic pressures created by COVID-19.

Short take: It will be interesting to see if these services can help consumers maintain access to liquidity during this economic disruption without slipping into usurious lending, which is a concern that U.S. regulators have already flagged for this fintech category.

Point, Merchants

The Department of Justice officially filed an antitrust lawsuit to block Visa’s planned acquisition of Plaid.

Short take: I’m sure you’ve seen the volcano sketch by now (side note- keep your drawing skills sharp in case your work product is ever repurposed for a lawsuit), but the most interesting part of this story to me is the fairly obvious role that merchants played in encouraging/supporting the DOJ’s action. This quote from the lawsuit is straight out of merchants’ anti-Visa messaging document:

Thanks,

Alex Johnson