Big Tech is Now Focused on Financial Services

What happens when Apple and Google actually want to make money in banking?

At the beginning of 2020, Cornerstone Advisors asked bank and credit union executives which types of companies they viewed as the biggest competitive threats over the next decade. Coming in first place, with a whopping 61% of respondents selecting it, was Big Tech; companies like Apple, Google, and Amazon.

At the time, this fear of big tech struck me as a bit misguided. I mean sure, Apple had just released its credit card the year before and there were rumors that Amazon was maybe going to be launching a checking account, but none of these moves (nor earlier moves like Apple Pay and Google Pay) made me all that nervous because they didn’t seem to be done with the primary intention to make money. Big tech’s motivation for dipping its collective toe in the financial services waters appeared, to me, to be customer retention.

Take Apple as an example. It launched the Apple Card, in partnership with Goldman Sachs and CoreCard (among others), in order to make owning an iPhone an incrementally more valuable experience. The product’s uniqueness had nothing to do with the underlying plumbing; it was the integrated experience. Activating the card using your iPhone felt just like connecting a new set of AirPods. Setting the card as the default payment method in Apple Pay was as easy as breathing. And using it to buy other Apple products was unusually rewarding (3% daily cash back).

Apple wasn’t trying to dominate the credit card market. It was trying to continue to dominate the smartphone market.

And this is how I viewed all the other big tech companies — Google, Amazon, Facebook1 — nibbling at the edges of financial services. It was an ecosystem play.

And that is what I told nervous bank and credit union executives whenever we talked about big tech — don’t worry too much about it. It’s worth paying attention to, but not obsessing over They’re not trying to compete with you. They’re trying to compete with each other.

The best analogy I could come up with was Godzilla and King Kong.

Yes, gigantic monsters are real. And yes, they are rumbling through the streets of your city and knocking down buildings. But they aren’t here for you. They’re only vaguely aware that you even exist. They’re here to fight each other. Your job is to stay out of the way and not become collateral damage.

This analogy didn’t exactly set those executives’ minds at ease (nor should it have!) but it did give them a framework for thinking about the competitive threat posed by big tech and how that threat stacked up against less spectacular (but perhaps more dangerous) adversaries.

Consequently, I was pleased to see, between 2020 and 2022, the number of bank and credit union executives listing big tech as a top competitive threat for the coming decade decrease, while more salient threats like consumer-facing fintech companies and challenger banks shot up the ranks.2

And then, naturally, a bunch of stuff happened that made my advice to banks and credit unions look kinda dumb.

Specifically, the following things happened:

Apple acquired Canadian payments company Mobeewave for $100 million.

Google announced that it was creating a digital checking account called Plex, in partnership with a number of banks and credit unions, as part of a larger revamp of Google Pay.

Google abandoned its plans to launch Plex, as part of a strategic pivot towards selling to banks rather than providing banking products directly.

Apple announced a “Tap to Pay” feature, built on Mobeewave technology, that will enable iPhones to accept contactless payments.

Apple acquired UK fintech start-up Credit Kudos, which specializes in analyzing open banking data to make credit decisions, for $150 million.

Apple, reportedly, has started working on an internal project — codenamed Breakout — to bring a wide range of financial activities (payment processing, credit risk evaluation, etc.) in house rather than continuing to rely on partners.

What does all of this mean? Let’s break it down by digging into the deeper strategic challenges that Apple and Google have been dealing with for the past couple of years.

Apple

Around 2016, it became clear that Apple — which had only ever seen iPhone sales grow at a record-setting pace — was facing a new problem:

The 2016 slowdown in iPhone sales revenue, which happened in the wake of the release of Apple’s flagship iPhone 6, marked a saturation point. Put simply, in a world in which basically everyone owns an iPhone, convincing customers to buy an iPhone every 1-2 years is extremely difficult.

And so Apple pivoted. Services became the new buzzword in Cupertino and Apple launched a boatload of new offerings — financial services, gaming, news, fitness, streaming entertainment, etc. The goal in offering these add-on services was, at first, about differentiating the iPhone from competitors, in the same way that Apple’s integration of custom silicon chips into its hardware did back in 2010. The idea was that this increased differentiation would revitalize slowing iPhone sales.

But that didn’t work.3 And so Apple went further, as Ben Thompson explains:

Apple is, famously, vertically integrated; the company writes the software that differentiates the iPhones that it manufactures and sells for a profit. That does not mean, though, that the entire iPhone experience is integrated — there are significant amounts of modularity. … However, Apple can and has extended its integration into areas that were previously modular. … Services like Apple Card, Apple Arcade, and Apple News+ extend Apple’s integration forward with the goal of driving new revenue.

Apple’s new goal was to generate new sources of revenue (to offset flat iPhone sales) by extending its integration into the services that it offered and cutting out third-party suppliers that provide specific modules of functionality.

This reduced reliance on third parties had its limits, according to Mr. Thompson’s coverage of the Apple Card launch in 2019:

don’t be surprised that Apple is partnering with Goldman Sachs: the company (rightly) wants nothing to do with the regulations entailed by being a bank, even if it means sharing those lucrative transaction fees.

However, it turns out that Apple’s ambitions for vertically integrating its services offerings goes even further than Mr. Thompson thought, as Bloomberg recently reported:

Apple is developing its own payment processing technology and infrastructure for future financial products, part of an ambitious effort that would reduce its reliance on outside partners over time

Apple is developing its own processing system ... It’s also creating tools for calculating interest, rewards, approving transactions, contacting and reporting data to credit bureaus, accepting or rejecting applications based on its own risk assessments, determining and increasing credit limits, and handling transaction histories.

The first product that will rely on the new system is expected to be the upcoming “buy now, pay later” service. That feature, called “Apple Pay Later” internally, will have two parts: “Apple Pay in 4” for short-term, four-installment payment plans without interest and “Apple Pay Monthly Installments” for long-term payment plans with interest.

Apple is discussing using the in-house technology for the four-installment plan. Apple would continue to work with Goldman Sachs on the longer-term installment offering, which will also have a higher maximum lending amount.

It seems likely that Apple will stop short of actually becoming a licensed bank, but it also seems clear that Apple, through acquisitions like Credit Kudos and the building of its own proprietary payments processing and ledger technology, is intent on taking as many of the non-bank charter parts of its banking-as-a-service (BaaS) stack in house as it can.

In short, Apple wants to squeeze as much money out of financial services as possible.

Google

When Google officially announced its Plex checking account product, it was part of a larger relaunch of the Google Pay app. While Plex took up a lot of the headlines, the more important news was hiding in a new tab in the app labeled “Explore”:

The first truly new tab in Google Pay is the Explore tab, which is a place where Google will aggregate deals for you. By default, it will just surface generic offers here, but you will have the option to allow Google’s algorithms to analyze your transactions in order to customize what offers appear. In what appears to be a nod toward privacy concerns, it will offer you an option to opt in to a three-month “trial” of the service. Since it’s a free service to begin with, that “trial” consists mainly of a reminder prompt that will pop up asking if you want to keep using it.

This feature was similar to merchant-funded “boosts” within Cash App, but with the key difference that it was Google — the most sophisticated and successful purveyor of digital advertising in history — providing it.

Similar to Apple’s early ambitions in financial services, the revamp of Google Pay and the launch of Google Plex seemed designed to further reinforce Google’s core business rather than creating an entirely new profit center.

Then something weird happened — Google pulled the plug on Plex:

Google is scrapping its plans to offer banking services directly to users. The shift comes nearly two years after the company first announced its banking plans and several months after a key executive leading the project departed.

This decision was especially perplexing because, based on the available evidence, Google Plex was going to be a hit. According to research from Cornerstone Advisors, nearly one in five consumers said (in a 2021 survey) they would have opened a Google Plex account when it launched. Among Apple Pay and Google Pay users, 33% said they would open an account.

Weird right? Why would Google kill a product that was going to be successful on its own and that would have further reinforced its core money-making business?

Here’s a hint, courtesy of the Wall Street Journal:

[Bill Ready, head of Google’s eCommerce operations] was concerned that Plex could make other banks think that Google was out to compete with them since it played a lead role in building the product.

But that’s not a totally satisfying answer. Google was doing this in partnership with banks, including Citi, which had more than 400,000 consumers signed up for the waitlist. And it wasn’t like Google was just using those banks as BaaS partners in the background. Their brands would have been front and center with the customers that picked them. Google was just providing the generic mobile experience wrapped around the banks’ products.

So again, why did Google do this? Why did it reverse course with its bank partners on Plex in order to abandon a product that looked likely to succeed and strengthen Google’s advertising business?

To answer this, we need to look more closely at that advertising business.

On the surface, business appears to be booming:

Google parent Alphabet Inc. posted another quarter of strong sales growth, capping a year when profit nearly doubled … The company’s dominance in online search, video and internet ad sales made it one of last year’s leading beneficiaries of an upswing in digital advertising. Last year, small and large businesses alike flooded into the ad market in a bid to win customers who spent early parts of the pandemic sequestered in their homes.

However, despite this pandemic-fueled surge in digital advertising, not all has been well in the world of digital advertising in recent years. Just ask Facebook:

Facebook parent Meta said on Wednesday that the privacy change Apple made to its iOS operating system last year will decrease the social media company’s sales this year by about $10 billion.

The change being referred to is Apple’s App Tracking Transparency feature, which made it much easier (and thus more likely) for consumers to stop third-party apps from tracking their behavior, which reduced the targeting capabilities of advertising platforms like Facebook, which in turn hurt those platforms’ bottom lines.

For a variety of reasons, Apple’s new privacy feature didn’t hurt Google nearly as bad, which enabled it to step into the void left by Facebook and pick up significant growth. However, Google would be foolish not to look at the $10 billion hit that Facebook just took from Apple and not worry about its dependence on advertising revenue.4

In order to diversify, Google has made a major push into the public cloud computing market. How major? In Q4 of 2020, Google Cloud Platform generated $3.8 billion in revenue and still lost $1.2 billion dollars. In other words, Google spent $5 billion dollars in just 3 months in order to continue growing its cloud computing business. Since then, those losses have shrunk, but Google Cloud Platform is still not turning a profit because Google continues to invest in it so heavily.

What are they spending all that money on? Most of it is going into the obvious stuff — data centers and software to run in them and engineers to manage them. However, a decent amount of Google’s investment in cloud has been in hiring experienced executives to sell Google Cloud Platform into specific industries. Financial services has been an especially big focus, with the recent hirings of deeply talented financial services experts like Sam Maule, Zac Maufe, Yolande Piazza, and the man himself — Bill Ready.

So, to return to our original question, why abandon Google Plex?

Here’s my guess — Google believes that it can squeeze so much money out of financial services companies’ desire to move to the cloud and digitally transform themselves that it is more than happy to scrap a promising consumer product on the off chance that its existence might offend those same financial services companies.

They’re Looking Right at You

We’ve been talking about the threat of big tech in banking for decades.5 However, Apple Pay’s launch in 2014 was a pivot point for banks and credit unions. The fear of big tech went from hypothetical (What if monsters exist?) to real and highly specific (OMG, I can see Godzilla and King Kong fighting. They’re literally outside my apartment!) And while I thought this pivot was cause for mild alarm and that it certainly called for caution and close observation, I still didn’t think it was a five-alarm fire.

Now however? It’s a five-alarm fire. Apple and Google want to make real money in financial services by either partnering with you or competing with you.

The monsters are looking right at you.

So, what should banks and credit unions do? What should fintech companies do?

I don’t know, but here are some of the questions that I’d be thinking about:

What are the practical and regulatory limits on Apple’s Breakout initiative? There is plenty of fat to trim out of Apple’s current BaaS arrangements (cue Goldman Sachs’ executives shaking their heads vigorously), but I’ll be curious to see just how far Apple goes in bringing the financial services functions currently provided by partners in house. Building a payment processing system and a ledger seems like it’ll be expensive, but it’s certainly doable. Customer service for things like disputes should be a relatively easy extension from what Apple already does. But what about things like credit risk assessment? According to Bloomberg, Apple is considering using an “in-house risk assessment engine [that] would take into account consumers’ history as Apple customers, such as if they have routinely paid off purchases or ever had their credit card attached to iTunes or the App Store declined.” Danger, Will Robinson! FCRA compliance is no joke and I doubt Apple has the stomach to become a Consumer Reporting Agency.

Will Apple flex its anti-competitive muscles with banks and fintech companies? Apple introducing its App Tracking Transparency feature in the name of protecting consumer privacy, while knowing full well the impact it would have on its big tech competitors, was a surprisingly brutal exercise of its monopolistic power. Now that it seems clear Apple is really trying to make money in financial services, might they try making similar moves against banks and fintech companies? Like, for example, what is this about?

How will Apple’s investments in digital identity fit into all this? You know what wasn’t mentioned in the Bloomberg article on Breakout and was, in fact, quite conspicuous in its absence? Apple’s digital identity initiative, which has involved working with eight different U.S. states to add verified state driver’s licenses into Apple Wallet. Maybe this was just an oversight on the part of Bloomberg, but this would seem like an obvious component to Apple’s Breakout plan, particularly if Apple does move forward with a small dollar, pay-in-4 BNPL offering, which would require highly accurate, continual ID verification.

What will Apple’s next financial services acquisition be? When you study the history of Apple’s acquisitions, one thing that jumps out is that Apple doesn’t buy companies for their brand value or customer base.6 When Apple buys a company, it does so because that company has a specific piece of technology that Apple wants to fold into its own stack. This is exactly what Apple did with Mobeewave and what it is doing with Credit Kudos. My question is what’s next? Will it continue to be small fintech infrastructure providers that help accelerate project Breakout or will Apple break its own rule and take a big swing?

Will Visa and Mastercard be more likely to side with issuers over Apple moving forward? The history of Apple Pay is fascinating. Apple negotiated a deal with Visa and Mastercard that allows them to decide which issuers are able to have their cards in Apple Pay and to extract a 0.15% fee from issuers on each Apple Pay credit card transaction. Apple was able to secure these special concessions (which Google did not get) from the networks in exchange for not developing its own proprietary payments network. According to reporting from the Wall Street Journal, credit card issuers have started griping about these fees (particularly for recurring transactions) and are pushing Visa to make changes. Visa has, so far, been reluctant to push these proposed changes through, for fear of angering Apple. But, like, at what point is enough enough? Apple launched its own credit card that now competes with issuers’ cards in Apple Pay. It’s getting into BNPL. It’s bringing payment processing in house and launching its own mobile payments acceptance capability. At what point do the card networks decide to stop giving into Apple’s demands for special treatment and start siding more with issuers in these disputes?

How far up the stack does Google want to go? Google wants to be an infrastructure and software vendor for banks. It has made that abundantly clear. The foundation of its offering for banks is cloud computing and all of the data analysis and machine learning capabilities that tend to accompany it. How far beyond that do they want to go? Obviously Plex — a pre-built digital banking shell for banks to plug their checking accounts into — was a bridge too far, but how close to that end of the spectrum is Google willing to go? Would they build digital identity capabilities for KYC, similar to what Apple is doing? Would they build white label-able versions of their Google Pay budgeting and merchant offers for smaller banks to incorporate into their digital banking apps? And, on a related note…

Will Google get into BaaS? I asked this same question in my recent essay on banking as a service. It makes a lot of sense, strategically. And from a technical perspective, they built 90% of a BaaS platform, similar to a Unit or a Stripe Treasury, for Plex. The only difference is that instead of having a Google-designed fintech product on the front end, you would plug in a bunch of fintech apps. Google would simply act as the middleware, connecting banks (like the ones it left high and dry with Plex) with fintech startups (perhaps sourced from its investment arm — CapitalG). It could even go further by tying in its Android developer community to create the ultimate fintech development sandbox, which would have the pleasant side benefit of putting more pressure on Apple to better serve its app developers, a task that it continually struggles with.

Will Google let Google Pay languish? Beyond the strategic decision to cancel Plex, Google Pay has struggled to execute against its roadmap and, due to those struggles, to retain talent:

Business Insider spoke with ex-employees and learned that dozens of employees and executives have left the Google Payments team in recent months, including at least seven leaders on the team with roles of director or vice president. One of the employees Business Insider spoke to said, ‘Plex was entirely [Vice President] Felix [Lin’s] and Caesar [Sengupta's] brainchild,’ and now both of those executives no longer work at Google. Progress on the bank account has already been ‘slower than expected,’ according to the report, and without its two leading architects, Plex may be delayed.

Google Pay still exists today as a consumer-facing product. Will Google continue to see it a necessary component for Android to compete with iOS?Will Google give it a new strategic focus and direction? Will it continue to invest in it? Or will it eventually join the long list of products in the Google Graveyard?

Short Takes

1.) Bark and bite.

The CFBP is suing TransUnion and one of the credit reporting giant's longtime executives for allegedly continuing to employ deceptive sales and marketing tactics.

Short take: The quotes from Director Chopra regarding this action are something else. There’s been some idle speculation in fintech circles that the CFPB under Chopra is more bark than bite; all blog posts and no enforcement actions. Turns out, this CFPB barks and bites.

2.) BNPL, bumming me out.

Afterpay has recorded a huge blowout in its half-year losses after a surge in bad debts and other operating costs failed to offset a big increase in the group’s revenue.

Short take: This has been the story pretty much everywhere in BNPL land for the last 6 months to a year. The BNPL companies argue that the losses are due more to aggressive growth tactics than they are to the inherent quality of the asset class. Skeptics of BNPL, of which there are many, argue the opposite. I’m beginning to side with the skeptics. Coming out of the pandemic-fueled boom times, BNPL (as a lending asset) hasn’t been holding up great.

3.) ‘Orb Operator’ is apparently a real job.

Worldcoin promised to jump-start the global crypto revolution with an audacious plan: to give out digital money to all 7.9 billion people on Earth. To spread its crypto gospel across the planet, Worldcoin recruited a corps of “Orb operators” whose job it was to scan people’s irises — in order, they said, to keep people from claiming their payment multiple times.

Short take: Just promise me you’ll read this story and then go to all of the young people in your life (kids, younger siblings, nieces and nephews, whoever) and make them promise you that they’ll never become orb operators.

🎵 On the Road Again 🎵

Busy season for fintech nerds. Lots of travel, which means lots of humming Willy Nelson to myself while standing in line at airports.

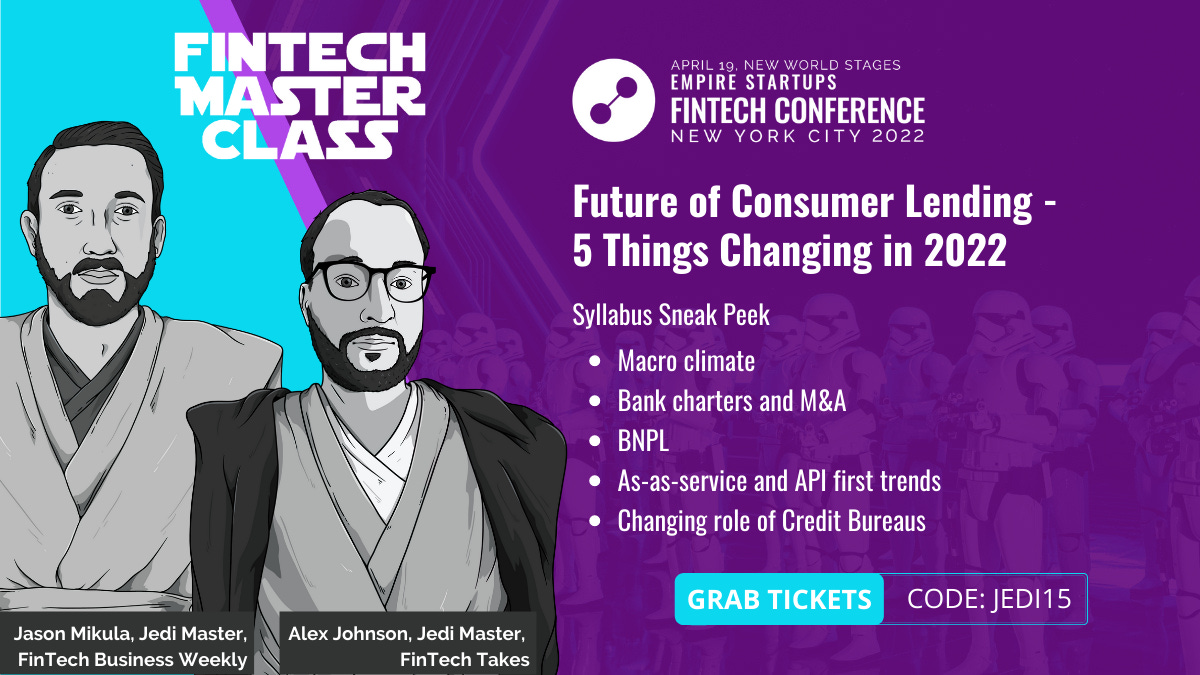

New York Fintech Week is next week and I will be there. I am thrilled to be co-presenting with Jason Mikula (of Fintech Business Weekly) on the future of consumer lending. If you’ll be around, make sure to stop by and say hi!

It’s worth delineating Facebook from the rest of FAANG. Apple and Google have launched successful payments products. Amazon has too, although it has never seemed as focused on it. Netflix has never tried. Facebook has tried and failed many times.

All of this data can be found in Cornerstone Advisors’ annual What’s Going on in Banking? report, which you should absolutely be reading, if you’re not already.

One of the main reasons that it didn’t work is that the ‘hardware + integrated ecosystem of services’ approach was less valuable in China, where consumers are already heavily reliant on the ecosystems provided by Alibaba and Tencent.

One way we know this is true — Google pays Apple something like $15 billion a year to not develop its own proprietary search engine for Safari.

The modern source of this anxiety might be this 1994 Bill Gates quote — “banking is necessary, banks are not”.

Kindly ignore the 2014 acquisition of Beats Electronics for $3 billion. That’s the exception that proves the rule.