Cash App is Culture (Part 1)

The challenge of building (and sustaining) a multi-product banking ecosystem.

Editor’s note: “Cash App is culture” has become common shorthand for explaining some of the more unusual decisions that Square has made in building out its marquee consumer banking product. Depending on your vantage point, this explanation either strikes you as profoundly true or deeply nonsensical. In this two-part post, I try to unpack exactly what “Cash App is culture” really means and why it’s critical to Square’s consumer banking ambitions.

Part 1 provides an overview and history of Cash App and an argument for why it is less of a consumer banking juggernaut than it may appear.

Cash App, Crushing It

Let’s start with some stats:

As of December, 2020, Cash App had 36 million monthly transacting active customers.

Gross profit per monthly transacting active customer reached $41 in the fourth quarter, +70% YoY. For customers that move beyond the app’s core P2P functionality and start using the Cash Card (Cash App’s debit card), average revenue increases by 3-4 times.

Due to strong network effects associated with P2P payments (give me your $Cashtag and I’ll pay you back for lunch), Cash App has maintained an average customer acquisition cost of less than $5 per customer. That’s astonishingly good compared to traditional banks, which would be hard pressed to acquire a new checking account customer for less than $250.

How Square Built Cash App

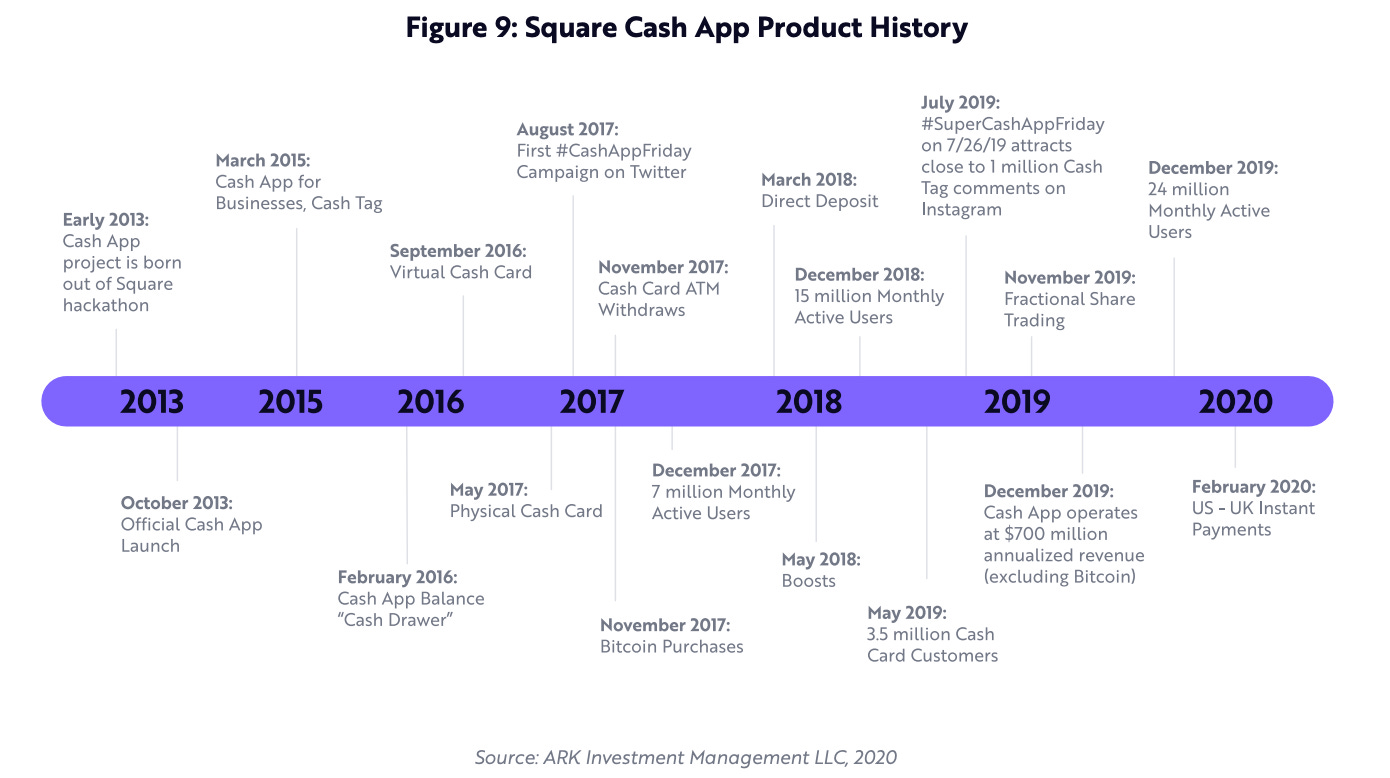

The Cash App (originally called Square Cash) was created during a company hackathon in 2013. The idea was to create a simple way for consumers to make electronic peer-to-peer payments for splitting a bill at a restaurant or sharing the costs of an AirBnB rental without using cash.

It wasn’t a new concept at the time — Venmo was well established and Google had just rolled out P2P payments functionality as well — nor was Square’s product especially sophisticated when it was first introduced.

And yet, Square has grown Cash App into a behemoth over the last 8 years. How?

As others have written1, the basic formula (which Square has executed almost flawlessly) can be broken into two steps:

Network — Cash App’s early traction came from younger unbanked and underbanked users, largely from the Southeast U.S., flocking to the app’s simple (and free) peer-to-peer payments functionality. The more users that joined, the stronger the network effects became, leading to Cash App vaulting past Venmo (in terms of both search popularity and downloads).

Utility — Once the network was established, job #2 was keeping users engaged and giving them reasons to bring (and keep) more of their money in the Cash App ecosystem. Square did this by rapidly adding and cross-selling new product features — a debit card, the ability to buy Bitcoin and do fractional stock trading, direct deposit, merchant rewards and discounts — turning the P2P app into full banking product (which was an especially good fit for their un/underbanked customer segments).

A Different Competitive Environment

Despite Square’s incredible progress, I think Cash App’s position in the market is far from unassailable.

A couple of reasons for this:

Low rate of active users. While 36 million monthly transacting active users is impressive, it’s still less than 50% of the total number of consumers that have ever used Cash App (approximately 80 million). High numbers of inactive users aren’t uncommon in the world of P2P payments, where one-time repayment interactions are common, but it’s still a problem if you’re trying to scale up into a full banking app.

Less affluent core market. Cash App’s target market is approximately 100 million potential customers, which consists of 65 million underbanked and 35 million in the 15-39 age bracket. Square has absolutely demonstrated an ability to serve these customer segments well (and cost effectively), but there are valid concerns about how profitable these segments can ultimately be given that many are less affluent than the segments dominated by banks today.2

Profitable Features vs. Popular Features. Cash App’s profit is driven by the use of the features that Square has layered on top of its core P2P functionality, but not all of these features are equally profitable. The largest percentage of gross profit for Cash App comes from subscriptions and services fees (Cash Card interchange fees, instant withdrawal fees, and interest income on customer balances). Unfortunately, only 25% of active users have the Cash Card, which unlocks all of this profitable subscription and service revenue. Meanwhile, Bitcoin is going gangbusters — more than 3 million users bought or sold Bitcoin in 2020 and more than 1 million customers purchased Bitcoin for the first time in January of 2021 — and yet it’s Cash App’s least profitable add-on service. In Q3 of 2020, Cash App made $1.6 billion in revenue on Bitcoin, which resulted in only $32 million in profit.

The temporary COVID boost. For both its merchant and consumer businesses, Square very smartly stepped in to help customers over the last year, facilitating PPP loans for merchants (Square extended $873m in total PPP loans across 80k businesses in Q2 2020, 60% of whom were new to Square) and using the Cash App to quickly disburse stimulus payments. However, this activity inflated growth and profitability metrics for Square in ways that are unlikely to sustain moving forward, as Square’s CFO, Amrita Ahuja, explained during a Q3 earnings call:

We do recognize, as you noted, the impact of the stimulus, which drove us to sort of peak levels in terms of stored funds. We were at about $2 billion in stored funds in July before seeing a decrease in October at about $1.75 billion in stored funds, down about 10% from July to October. And we think that that's likely related to inflows related to these sorts of government funds.

Additionally, it seems distinctly possible that revenue growth from fractional share trading and Bitcoin will also slow as we all start to leave our houses and need less creative ways to avoid boredom.

All of these smaller concerns feed into a larger question — will Cash App be able to create a durable, highly profitable, multi-product banking ecosystem?

You tend to see smart folks in the fintech space compare Cash App to big banks like Chase. This is an easy comparison to make given the scale that Cash App has so quickly achieved.

The assumption sitting below this comparison is that Square will be able to leverage Cash App’s user base in the same way that Chase has — cross-selling more and more profitable products (unsecured installment loans, credit cards, even mortgages) until their average revenue per user equals or exceeds Chase.

Here’s the problem.

Chase became Chase in a fundamentally different competitive environment, where distribution moats (i.e. branches) and high switching costs were significant and durable advantages. Those were the days when primary bank status meant something; customers weren’t going anywhere and Chase knew that, so they could hammer away at them with generic, badly pitched cross-sell offers until the customers gave in.3

Those days are over. Thanks to the proliferation of digital account opening and the emergence of payroll-enabled direct deposit switching, the concept of a primary bank account has become much more fluid. Consumers can now maintain a variety of bank accounts simultaneously and automatically move funds between them. Indeed, according to research from Cornerstone Advisors, 35% of U.S. consumers already have more than one checking account, led by the 42% of Millennials who have two or more accounts.

The cross-sell advantage that used to accrue to incumbents is no longer relevant because the very concept of an incumbent service provider has been disrupted.

In today’s competitive environment, the technological forces that have enabled Cash App to compete head to head with Chase — easy digital account opening, peer-to-peer network effects, low switching costs — are the same ones that could enable the next disruptive fintech company to quickly challenge them.

This is the problem with technology. The competitive advantages that it confers quickly become commoditized.

Editor’s note — Part 2, in which I explain how investments in culture can provide sustainable differentiation where technology may not, can be found here.

Sponsored Content

Fintech Spring Meetup: Face-to-Face meetings, no masks required! No keynotes. No webinars. Just 15-min online meetings to connect with others in Fintech. Join 1,000+ others for 10,000+ meetings! Qualifying Retailers & Merchants/Banks & Credit Unions can join for free! June 15-17. Get Ticket Now.

Short Takes

(Sourced from This Week in Fintech)

If you have to work this hard, it’s not working.

Revolut applied for a U.S. bank charter after announcing last week that it was suspending operations in Canada.

Short take: Given the challenges that European neobanks have had expanding into North America and Revolut’s recent decision to give up on Canada, this application for a U.S. bank charter feels a bit like the couple who decide to get a pet just as their relationship really starts to fall apart. “We love each other. THIS CAN WORK!”

Can’t pay people to switch.

The UK’s Incentivised Switching Scheme, which provided a £275 million incentive for small businesses to switch from Royal Bank of Scotland to neobanks, fell short of its target.

Short take: Couple things here: 1.) As an American, I admire the hell out of how UK regulators handle their business. “You make taxpayers bail you out? We’re gonna pay your customers to switch to your competitors!” 2.) Even funnier though, it didn’t work! Less than half of the target number of SMEs actually switched.

Fintech moves fast.

The New York Department of Financial Services’ probe into Apple Card led to no findings of gender discrimination.

Short take: This feels like it happened one million years ago:

But it was, in fact, less than two years ago. Not surprising that the NYDFS came to this conclusion, but a bit discouraging that it took this long. Regulators need to pick up the pace. Fintech moves fast!

Alex Johnson is a Director of Fintech Research at Cornerstone Advisors, where he publishes commissioned research reports on fintech trends and advises both established and startup financial technology companies.

Twitter: @AlexH_Johnson

LinkedIn: Linkedin.com/in/alexhjohnson/

Essential resources for deeper dives into Cash App’s history and business model: Hip to be Square by Marc Rubinstein, CashApp Is King by Aika Ussenova, The Square Opportunity by Jax Vullinghs, A Deep Dive Into The Cash App's Growth Machine by Alan Tsen, and Square Valuation Model: Cash App’s Potential by Maximilian Friedrich.

I think this problem will become less severe over time as banks’ core customer segments age out of being prime banking customers and Square’s younger customers age in.

Or, in the case of Wells Fargo, skipping that step and just opening new accounts on the customers’ behalf.