The Fintech Acquisition Boom of 2021

Why it's happening and the secrets to doing it well.

Our story starts on January 12th, 2021.

Almost exactly a year earlier, Visa had announced that it was acquiring Plaid for $5.3 billion. The reaction, at the time, was almost universally positive for Plaid. The 25-50x revenue multiple that Visa had agreed to value Plaid at was seen as a huge validation for both Plaid specifically and for the fintech ecosystem more broadly.

And yet, one year later, Plaid and Visa announced that the deal was off1:

And the reaction from the fintech ecosystem was, again, overwhelmingly positive!

The consensus was that Plaid would be better off continuing to build on the momentum that it had seen over the course of 2020 than to be acquired for the previously-impressive-but-now-obviously-pedestrian sum of $5.3 billion.

And that consensus looks, so far, to be right on the money. Four months after calling off the acquisition, Plaid announced $425 million in new funding which valued the company at more than $13 billion.

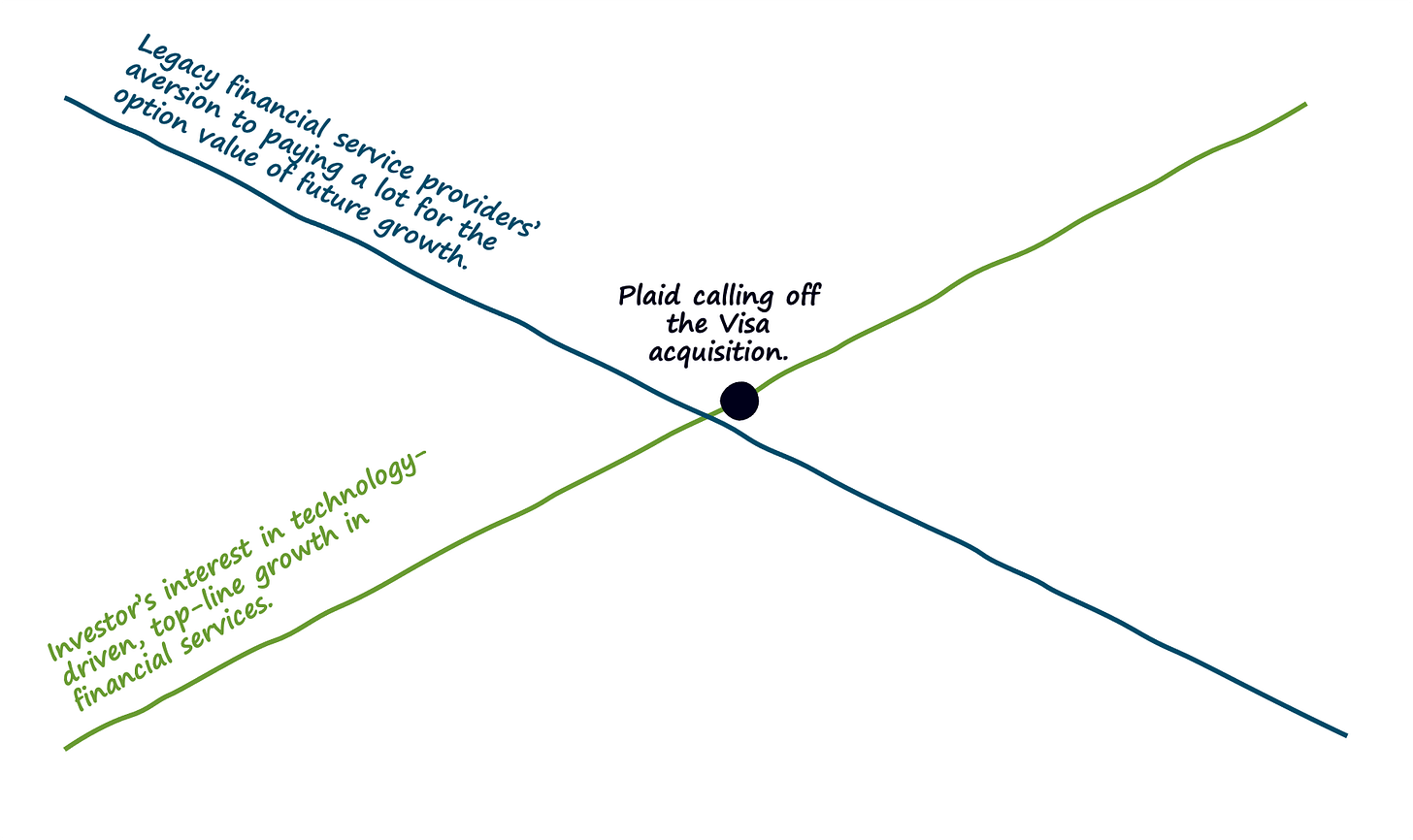

With the benefit of a little hindsight, it appears that 2020 was the year in which two different trend lines intersected:

Investors in the private and public markets have increasingly been valuing financial services companies based not on their current earnings or profitability, but rather on their future top-line growth potential. This has, obviously, been the driving factor behind the insane growth in VC investment in fintech. However, it’s also been the driver behind legacy financial services providers’ increasing focus on technology spend and their desire to tell more of a tech-forward story to their shareholders.

This has led to our second trend — a weakening of those same providers’ historical aversion to paying high multiples for acquisitions based primarily on the option value of future growth.

The result, as Frank Rotman, Founding Partner at QED Investors, explains, is an increasing willingness to make such acquisitions:

A company is worth the intrinsic value of what it’s worth today and the option value of what it’s worth in the future. And the problem with most bank acquisitions in the past is that they worried so much about the overhang associated with the goodwill of a company. All they were willing to pay was the intrinsic value of what a company was worth at that moment and that’s why they were never competitive. And now they’re realizing that they’re being rewarded by the market for having a tech strategy and being rewarded for tech spend and for driving top line revenue growth. So all of a sudden banks have realized that the value equation in the market has shifted which is why the purse strings are opening up.

That’s great, but of course the challenge is that all of those acquisition targets are, by dint of private market investors’ wild enthusiasm, seeing faster and faster growth in their valuations, which can quickly put them out of reach as viable acquisition targets.

So the question for banks and other legacy financial services providers is how quickly can they square the circle between their natural discomfort with tech-priced acquisitions and the rapidly spiraling valuations of fintech companies?

Judging by the actions of legacy financial services providers in 2021 so far, the answer would appear to be quite quickly. Here are just some of the fintech acquisitions that they have made this year:

JPMorgan Chase acquired 55ip, a provider of automated tax-smart investment strategies.

JPMorgan Chase acquired wealth management startup Nutmeg.

Visa acquired European open banking provider Tink for €1.8 billion.

Cross River Bank acquired lending risk management tool PeerIQ.

Fifth Third Bank acquired Provide, a platform for healthcare practices.

JPMorgan acquired OpenInvest, a personalized consumer ESG investing platform.

Visa acquired cross-border payments provider Currencycloud, valuing the business at £700 million.

Bill.com acquired competitor Invoice2go, in a stock and cash transaction valued at approximately $625 million.

Lloyds Bank acquired digital wealth platform Embark Group for £390 million.

US Bank acquired the business expense and CFO software provider Bento Technologies.

The National Bank of Canada took a majority stake in open banking and data-sharing startup Flinks for C$103 million.

Mastercard acquired Danish open banking tech provider Aiia.

Goldman Sachs announced that it will acquire home improvement and healthcare lender GreenSky in an all-stock deal valued at $2.24 billion.

JPMorgan Chase acquired college planning platform Frank.

But what exactly is the strategy behind these acquisitions? How are market incumbents determining which companies to acquire and how are they becoming comfortable with the valuations? Why are fintech companies open to acquisitions, especially given the current love affair that fintech is having with private equity?

To answer these questions, I took a deeper look at Fifth Third Bank’s acquisition of Provide. I spoke with Frank Rotman of QED Investors (QED was an investor in Provide), Ben Hoffman, Chief Strategy Officer at Fifth Third, and Dan Titcomb and James Bachmeier III, the Co-founders of Provide.

I’ve distilled our conversations down into a few key lessons that any financial services company should think about when considering an acquisition.

Buy. Partner. Build. In that order.

The first challenge for banks in making fintech acquisitions is shifting away from the build-everything-in-house mentality that has dominated banking for decades. Fifth Third is ahead of the curve here, as Ben Hoffman explains:

We have never pretended that banks are closed systems. For a lot of our peers, this idea that we’re going to leverage other people’s distribution or other people’s product is new and disruptive. Our view is that banking has been that way for a long time. Whether you think about indirect auto or brokered mortgage, go on down the list, there’s a lot of business that we do where we are either the manufacturer but not the distributor or the distributor but not the manufacturer. As the pace of innovation accelerated in the fintech world, it wasn’t hard for us to look at that space and see opportunity and find ways to plug in.

This mentality comes from the very top. On a recent earnings call, Greg Carmichael, CEO of Fifth Third, said “we have a buy-partner-build strategy”, which Ben Hoffman elaborated on for me:

When we say buy what we mean is if something exists off the shelf, we’re going to use that. That means acquiring, but it also means licensing. If it doesn’t exist off the shelf as you want it, go find a world-class expert in the space and partner to build it together. And only if that doesn’t happen do we build.

TL;DR: Acquisitions only work if the acquirer starts from the assumption that there are things that they can’t and/or shouldn’t build themselves.

You have to build the infrastructure.

The next challenge for banks is recognizing that successful acquisitions require more than just a willingness to open up the checkbook, as Frank Rotman explains:

Acquisition is a skill. Organizations are either structured to do it and know how to do it or they don’t. If you are going to acquire companies, you need to build up the muscle to do it well. To do that, a company should practice on buying smaller things first and then take bigger swings once the right skills are in place.

These muscles are, candidly, underdeveloped at most banks, which places the banks that are good at it in an advantageous position. James Bachmeier III elaborates:

It’s a unique challenge to acquire a fintech company. You need to have the people and systems in place and most banks today don’t have them right now. Fifth Third is five years ahead of everyone in installing that infrastructure [and it’s no joke].

TL;DR: It takes years of practice to get good at acquiring companies and fintech companies present unique challenges that most banks aren’t ready for.

The hardest problem is what happens after.

One of the characteristics of great acquirers seems, ironically, to be a recognition of just how freaking hard it is to make them work after the transaction is completed. The reason it’s so hard, according to Frank Rotman, is because of the culture that exists in most big companies:

The challenge that big organizations have is that anything new that comes into the system generates a strong counter-reaction. There are a lot of antibodies. Culture is how you get work done, and ingesting a brand new company with very different values and very different ways of getting work done is really hard. Banks have a lot of antibodies.

Banks that are realistic about these challenges and are willing to do the hard work to overcome these ‘antibodies’ stand the best chance of being successful. Ben Hoffman explains:

We are not a business, at our core, that is growing 20, 30, 40, 50 percent a year. So you have to believe that when you acquire a company like this that you can sustain, for that portion of your franchise, that type of growth rate. And you have to engage in an integration model that not only prevents you from getting in your own way, but actually enables and turbocharges the growth of that franchise. That was the longest conversation that we had. How do we make sure to make this franchise successful within our four walls? That was a longer conversation than ‘do we think this franchise will be successful?’

TL;DR: A lot of acquisitions that make tremendous sense on paper end up failing because the acquirer underestimated the amount of work and organizational alignment required for the acquired company to thrive within its four walls.

Look out for the employees.

An important, yet under-discussed factor in acquisitions is the impact on the acquired company’s employees.

It matters.

It matters when investors are evaluating the acquisition offer, as Frank Rotman explains:

A lot of times it comes down to looking at how employees and other common shareholders are going to be treated in the transaction and afterwards by the acquirer.

It matters, on a deeply emotional level, for the founders of the acquired company, as Dan Titcomb describes:

Our employees were a tremendously large component of this decision. When we talk about the liquidity risk [of running a lending business], no matter how small that risk is, what we’re really thinking about in the back of our minds is the risk that 150 people on our team end up out of a job.

And it matters to the acquiring company, in terms of both retaining talent and maintaining a strong recruiting pipeline moving forward, as Ben Hoffman told me:

One of our concerns, when we closed this deal, was that their recruiting pipeline would see some fallout. People who were looking to leave a large bank and go work at a fintech would now be looking at another large bank. But what we’ve seen is actually the opposite, which surprised me, but the feedback we’re getting from the market is that the proposition of Provide as an employer and what you can achieve there has remained the same, but there’s now a baseline level of stability being a part of Fifth Third.

TL;DR: Everyone involved in an acquisition should care about the impact that the transaction will have on the employees of the acquired company. If that’s not true, you have a problem.

Relationships matter.

The concept of relationships comes up a lot when you talk to people about acquisitions; the date-before-you-get-married trope is a common talking point.

For good reason.

Frank Rotman puts it simply:

The better the two companies know each other, the fewer surprises there are throughout the due diligence process.

In the case of Fifth Third and Provide, the acquisition was an outgrowth of a deep, pre-existing relationship, as Ben Hoffman describes:

We were on their cap table. We had an operating partnership. We had $400 million of Provide-originated loans on our books and of that $400 million, 70% of those customers we had multi-product relationships with. In addition to that operating partnership, well prior to making our initial equity investment, we got to know Dan and James personally.

And it wasn’t a one-way street. Provide, from the very start, took a very deliberate, relationship-first approach to dealing with their bank partners, as Dan Titcomb shared with me:

We’ve seen V1 online lenders rise and fall and there was a real hubris at the height of that first wave in how those lenders treated their bank partners. We had the luxury to be just starting out when that was happening and being able to learn from that era.

TL;DR: Perhaps the biggest secret to successful acquisitions turns out to be rather boring — build trusted relationships by treating people with respect and taking the time to get to know them. This is a lesson that many fintech companies and banks have, in the past, failed to heed. Hopefully the fintech acquisition boom of 2021 will prove that both sides have learned.

Sponsored Content

Fintechs have helped millions of people increase their financial well-being, but for many of these users, insurance continues to be a financial stressor. Users are increasingly turning to the financial services they trust for a solution that solves their insurance needs.

Savvy is the leading solution in the market that enables fintechs to build a white labeled, embedded insurance offering. Savvy helps fintechs build best-in-class insurance experiences that bring real value to their users. Turn insurance into a monetization engine that delivers users meaningful savings through a highly differentiated, native experience.

Connect with Savvy about a custom solution by following the link below!

Short Takes

Invest in female founders.

Barclays and Anthemis opened up a $30M fund for female founders in the UK and Europe.

Short take: Venture funding for female founders hit a three-year low in Q3 of 2020 as the pandemic had a disproportionately negative effect on women and minority-founded businesses. WE NEED TO FIX THIS!

Modern loan servicing … thank God.

Peach Finance, a loan servicing platform, raised a $20 million Series A.

Short take: Fintech has, historically, had a bias towards the front-end of the lending process — acquisition and origination and account opening were sexy (and profitable). The back-end — servicing and collections and recovery were largely ignored. I love seeing fintech innovation (and funding) finally coming to this area.

Why do you keep hitting yourself?

Bank of America launched Balance Connect, a new feature that helps users avoid overdraft fees … for a $12 fee.

Short take: Paying a $12 fee to avoid paying a $35 fee is better in the same way that having your brother sit on your chest and hit you with your own hands while repeatedly saying ‘why do you keep hitting yourself?’ is better than having him just straight up punch you in the face. It probably does hurt less, but it’s much more insulting.

Alex Johnson is a Director of Fintech Research at Cornerstone Advisors, where he publishes commissioned research reports on fintech trends and advises both established and startup financial technology companies.

Twitter: @AlexH_Johnson

LinkedIn: Linkedin.com/in/alexhjohnson/

The precipitating factor behind the Plaid — Visa deal falling apart was, obviously, the Department of Justice’s antitrust lawsuit against Visa.