Reimagining Mortgage Servicing

It's not technically broke, but we badly need to fix it.

Do you ever look at something in the world that works OK the way it is and get deeply annoyed because, despite the fact that it works, it still feels like a wasted opportunity?

Like, imagine living in an alternate universe where LeBron James was the world’s greatest handball player.1 It’s not completely inconceivable nor is it bad, in an objective sense, but every time you saw him you’d say to yourself ‘man, I bet that guy would be GREAT at basketball’.

This is how I’ve come to feel about the mortgage servicing process in the U.S.

It’s incredibly complex and there are valid reasons for why it works the way it does, but every time I sign up for auto payments for a mortgage loan2 with a company that I’ve never heard of and that I had no part in picking, I can’t help but feel like it’s the biggest missed opportunity in financial services.

And so, I present to you a story about mortgage servicing, in three parts.

Part I: How we got here.

Home ownership has always been a central tenet of America’s civic religion and its virtues have been preached by those at the very top.

Thomas Jefferson:

The small landowners are the most precious part of the state.

Franklin Roosevelt:

A nation of homeowners, of people who own a real share in their land, is unconquerable.

Bill Clinton:

Homeownership, home building, home sales, home mortgages, and home values will once again be the rising tide that lifts all of America’s boats.

And my personal favorite3 — Calvin Coolidge:

No greater contribution could be made to the stability of the Nation, and the advancement of its ideals, than to make it a Nation of home-owning families. All the instrumentalities which have been devised to contribute toward this end, are deserving of encouragement.

That last bit is key:

All the instrumentalities which have been devised to contribute toward this end, are deserving of encouragement.

The modern U.S. residential mortgage market is the sum of a great deal of financial and regulatory engineering designed transform the reality of home ownership into something as broadly appealing as possible.4

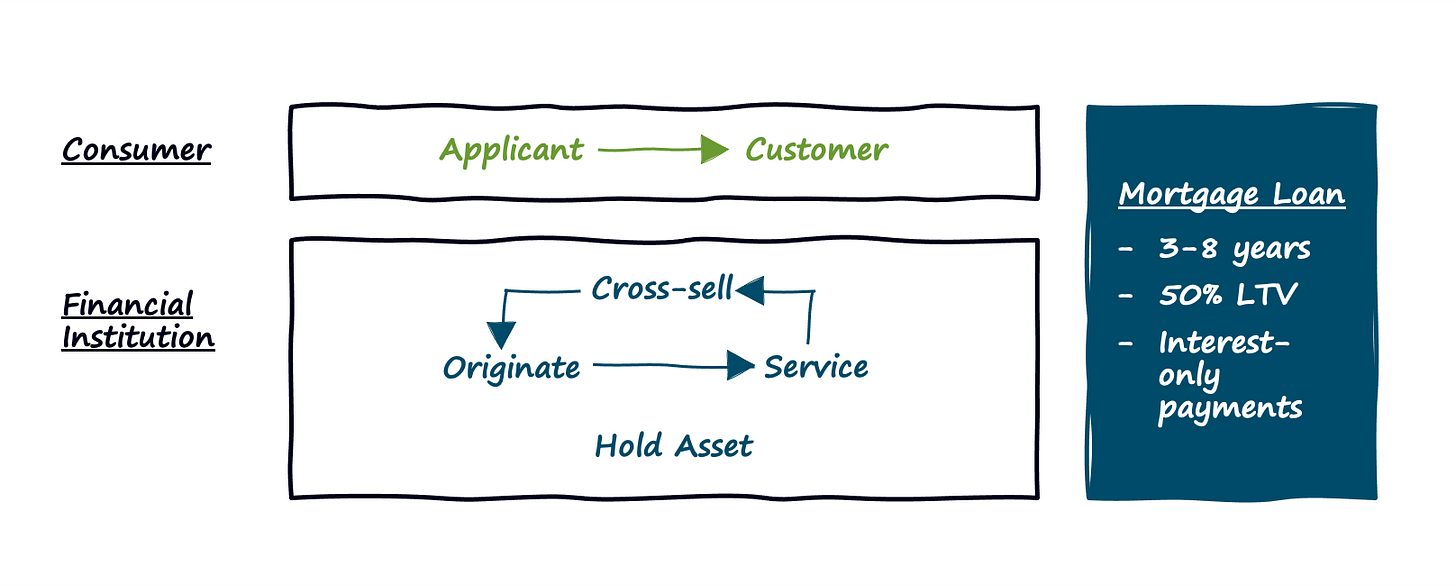

Prior to this transformation, in the early 1900s, an American family buying a house would typically pay 50% of the total purchase price upfront and finance the remaining 50% on a 3-8 year term at a rate of around 5%. Crucially, the payments made towards the mortgage only covered the interest (not the principal) and at the end of the loan term the borrower would either pay off the principal or refinance and take out a new 3-8 year loan.

Then came the event which transformed the U.S. mortgage market (and most other aspects of American life) — the Great Depression.

With home values crashing and lenders refusing to refinance existing loans, mortgage default rates shot through the roof. Between 1931 and 1935, 250,000 homes were foreclosed on a year.

So the government stepped in. It purchased one million defaulted mortgages and converted them from variable, short-term interest-only loans into fixed-rate, 20 year, fully amortizing mortgages (i.e. payments went towards the principal and the interest), which were significantly easier for Americans to repay.5

The downside was that lenders hated them. Protecting borrowers from interest rate and capital risk was great … for borrowers, but it put lenders in the tough position of keeping these mortgages on their books for 20 years, with no ability to refinance unless it was to the borrower’s advantage.

Thus, the Federal National Mortgage Association was created in 1938. Today, we call her Fannie Mae.

Fannie Mae’s purpose was (and, along with Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae, remains) to buy mortgages from the lenders that originate them and securitize them for investors in the secondary mortgage market, thereby injecting needed liquidity and allowing lenders to redeploy that capital as new mortgage loans.

This regulatory innovation marked the definitive pivot point in the history of the U.S. mortgage market. Mortgage lending went from a simple, profitable business that could be conducted holistically by banks to a highly complex business that can, by design, only be profitable when each step in the process is conducted by different set of highly specialized companies and government agencies.

Today, the $11 trillion U.S. mortgage market flows through brokers (responsible for finding borrowers), banks and non-bank lenders (responsible for underwriting and originating loans), government-sponsored enterprises (the technical term for Fannie, Freddie, and Ginny), investors (these are companies and individuals that buy mortgage-backed securities from the GSEs or directly from lenders), and servicers (responsible for collecting and distributing loan payments).

In pursuit of the liquidity necessary to fuel the dream of ubiquitous home ownership, the U.S. government transformed a straightforward product and process that looked something like this:

Into a machine that would make Rube Goldberg proud:

Now, to be clear, complexity isn’t necessarily bad and the U.S. government’s transformation of the mortgage has been hailed as “something that Rumpelstiltskin would envy. They took the worst possible investment – a 30-year fixed-rate fully prepayable mortgage – and turned it into the second most liquid instrument in the world, just behind Treasuries.”

But there have been casualties along the way6 and one of the most glaring (to me) is the complete degradation of the mortgage servicing experience.

Part II: The horror! The horror!

Mortgage servicing is, in the simplest terms, the process of collecting monthly loan payments from borrowers, managing borrowers’ escrow accounts, paying out funds to investors (the owner of the mortgage or mortgage-backed security) in the form of principal and interest, and dealing with any problems (loss mitigation, foreclosures, etc.) along the way.

The process is, as everything in mortgage lending tends to be, highly regulated, with the GSEs providing the primary guidance on how conforming loans (loans that meet their specifications for purchase) are to be serviced.

A few lenders directly service the mortgages they themselves originate. However, a majority of originators either contract that work out to sub-servicers (companies that specialize in mortgage servicing) or sell the mortgage servicing rights (MSRs) for the loans to third-party servicers.7

For third-party servicers, the primary source of revenue is a fee of 25 basis points per payment and additional fees for dealing with problems like late payments.

Servicers need to balance this revenue against significant costs (compliance costs, in particular), which has resulted in an industry dominated by a few large companies that prioritize scale and operational efficiency over everything else. Or, as a former executive at one of the largest mortgage servicers in the country told me, “any project that wasn’t about cutting costs was a no go.”

You’ll be shocked to learn this, but mortgage servicers’ narrow focus on operational efficiency hasn’t resulted in an abundance of satisfied customers.

According to J.D. Power, the average NPS for a primary mortgage servicer is 16. SIXTEEN. That’s bad. That’s like, your-laptop-will-spontaneously-burst-into-flames-if-you-stare-at-that-number-for-too-long bad.

It’s not surprising though, really.

Think about it from the customer’s point of view.

You close on your mortgage and buy the house of your dreams. Your lender tells you that in the next month or two you’ll find out the name of the company that you will be making payments to for the next 30 years.

You’ll find out when they send you a letter in the mail! So make sure to watch out for generic, plain-looking letters from companies you’ve never heard of. One of them is your new mortgage servicer telling you where to send your payments.

In that letter is a set of instructions for creating an account and setting up your payments. It will require you to wade through the oldest still-functioning websites in the financial services industry and tussle with mobile apps that Apple and Google, in good conscious, never should have allowed into their app stores. You may even need to send a fax.

Once all of this is set up, guess what? Your mortgage servicer can change at any time! You just get another generic letter mailed to you informing you that the MSR associated with your loan has been sold and then yet another letter introducing you to your new servicer with instructions for how you can *easily* set up your new account and schedule your payments.8

Unsurprisingly, this transfer process is especially frustrating to customers, with J.D. Power finding that 54% of first-time home buyers said they were confused, angry or irritated when their loan servicing was transferred.

And all of that doesn’t even touch on the hell that customers go through when they hit some sort of financial difficulty and have to work with their servicers to manage their payments or enter into a forbearance program. This anecdote, from a Wall Street Journal article on home owners navigating the financial stress of the pandemic, provides a glimpse:

“I’m frustrated and scared,” said Chris Colgan, a real-estate agent from Northern Virginia. He said he called his servicer some 15 times in the past month. Mr. Colgan … started calling his mortgage company, NewRez LLC, in early March. He filled out an online form about three weeks ago explaining that his commission-based job might be put on hold as potential home buyers stay out of the market. Someone would get back to him within three days, the company’s website said, but Mr. Colgan said he never heard from anyone.

Part III: How do we fix it?

Hopefully, by this point in the story, I’ve convinced you of the need to improve the mortgage servicing experience for borrowers.

The last question that needs to be answered is how can we do that?

I see three possible approaches, listed below in ascending order of ambition.

1.) Hang on to those servicing rights!

The easiest approach is for mortgage lenders to hang on to the servicing rights for more of the loans that they are originating. This would be a big shift for many lenders today, but it’s absolutely possible. Indeed, the largest mortgage lender in the country (Rocket Mortgage) has already gone down this path:

In 2010, we made the strategic decision to invest in loan servicing. Servicing the loans that we originate provides us with an opportunity to build long-term relationships and continually impress our clients with a seamless experience. We employ the same client-centric culture and technology cultivated in our origination business towards our servicing effort. The result is a differentiated servicing experience focused on client service with positive, regular touchpoints and a better understanding of our clients' future needs.

This talk of “long-term relationships” isn’t marketing fluff. It’s cold and calculated business strategy. Retaining servicing rights and closely integrating the origination and servicing processes has allowed Rocket to kick its competitors’ asses when it comes to retention and refinance:

Servicing a client's loan allows us to remain in contact with our clients and stay current on their financial needs. For example, we rely on insights gained from servicing to offer solutions to clients when they can benefit from a more cost-effective mortgage. As a result of this approach, in 2019 when clients chose their next mortgage, we had overall client retention levels of 63% and refinancing retention levels of 76%, which is approximately 3.5 times higher than the industry average of 22%. In 2020, our year to date average has grown to nearly 75% overall client retention.

And here’s a cool wrinkle — Rocket still sells the loan assets that it originates, even though it hangs on to the servicing rights. This allows it to control the end-to-end customer relationship while offloading the credit exposure and maintaining its capital efficiency:

Our business has minimal credit exposure as we sell our mortgage loans to investors in a matter of days. We also do not have direct credit exposure to the servicing portfolio since we do not own the underlying loans that are being serviced.

2.) Modernize mortgage servicing software.

A slightly harder, but promising approach is to use software to drive down the costs of loan servicing, which can be surprisingly high for an already low margin business, as Andreessen Horowitz points out:

The average cost to service a performing loan has risen $59 to $156 from 2008 to 2013. For non-performing loans over the same time period, it’s jumped from $480 to $2,350. Why? First, there are hundreds of pages of regulation that differ on a state-by-state basis. Most servicers were built in the 1960s and still operate on blue screens. As more regulation was enacted over the years, it was nearly impossible for the servicers to update their software, so more bodies were thrown at the problem. As a result, mortgage servicing is an extremely low-margin business. A new software servicer will reduce the transaction cost (software handles most tasks, not people in call centers), reduce credit loss (by helping consumers avoid foreclosure), and increase returns. Furthermore, if the consumer is comfortable being more honest and transparent with a servicer they believe will present them with their best options, it should take excess costs (like legal expenses) out of the system and lead to better outcomes for all parties involved.

Upgrading this software is a tall order — the top 25 mortgage servicers in the U.S. control roughly 80% of the market and approximately 20 of those 25 servicers use the same legacy software system — but there are a number of fintech companies working on it.

Two stand out, in terms of both the progress they’ve made and the divergent paths they’ve chosen to follow.

The first is Valon Mortgage, which is a full service mortgage servicer built on top of a modern, proprietary technology stack:

[Valon] built a mobile-first servicer that will elegantly handle today’s reality (e.g., check your balance, understand your escrow account, present forbearance plans understandably) and scale for the complexity sure to come in the future (e.g., model new forbearance plans, incorporate new regulations, etc.). Valon recently became the first new servicer to obtain Fannie Mae licensing with a new proprietary system.

The second is Brace, which rather than becoming a servicer has chosen to build a software stack for servicers, with an emphasis on non-performing mortgages:

“Right now, servicers are forced to use decades-old technology to manage millions of US mortgages—a problem that gets much worse for servicers who manage borrowers that are non-performing,” said Eric Rachmel, CEO of Brace. “We take a different approach that is focused on modernizing the servicing process with software modules and services for mortgage servicing infrastructure, instead of the one-size-fits-all servicing system that often misses important nuances.”

3.) Layer an entirely new customer experience on top.

This last approach is, admittedly, a bit of a long shot, but I would be remiss in my analysis of the mortgage servicing space if I didn’t step back and consider the following scenario:

Let’s say that Amazon — the self-stated ‘most customer-centric company on Earth’ and a company that is willing to invest ridiculous amounts of money over extremely long time horizons — suddenly got into the mortgage servicing business. What would the resulting experience look like? How would Amazon productize a 30-year long relationship that revolves around the single biggest financial asset in most consumers’ lives and the single most emotionally resonant setting in most consumers’ lives?

I’m guessing that A.) it wouldn’t look anything like today’s mortgage servicing experience, and B.) it would have very little to do with loan repayment.

All the value would be layered on top.

Personally, I think it would look something like an incredibly souped-up version of IFTTT — an intelligent automation hub that continuously optimizes every decision that relates to home ownership, occupancy, or monetization. Everything from managing schedules and collecting payments for vacation rental season to persistently searching for even the smallest price improvements for utilities, insurance, and maintenance services. The mortgage servicing hub would connect in to the customer’s network of smart home devices so that these decisions could be informed by real-time data on the state of the home and its occupants. It would intelligently integrate the evolving financial assets home ownership into these decisions as well so that, for instance, choices about home repairs and remodels could be made based on the customer’s current equity in the home and the loan options that equity could unlock.

And ohh yeah, it would collect mortgage loan payments.

Sponsored Content

Nexus is a high-end partnering event for fintech decision makers, brought to you by the team behind LendIt Fintech. This is where bank and credit union executives, investors and fintech executives come to pitch, partner and get deals done in a series of high impact meetings and networking events. There are no panels or keynotes. Just business.

Short Takes

Square deal.

Square announced that it will acquire Australian buy-now-pay-later lender Afterpay, in an all-stock deal valued at $29 billion.

Short take: There are lots of takes to be had on this one. Mine can be found here, but you should also read Marc Rubinstein, Ron Shevlin, Alan Tsen, Simon Taylor, and Jason Mikula.

Easier button.

Bloom Credit launched automated furnishment to the three national credit reporting agencies.

Short take: Data furnishment can have a huge impact on fintech customers’ credit scores, but it’s rarely at the top of any fintech company’s product roadmap. Hopefully solutions like this make that prioritization decision easier.

Democratizing credit.

Banking as a service provider Synapse plans to offer its customers white-labeled credit products.

Short take:

Featured Research

Here are the five fintech trends from July that caught my eye.

Intrigued? Check out Fintech Fire Alarms, for the details.

Alex Johnson is a Director of Fintech Research at Cornerstone Advisors, where he publishes commissioned research reports on fintech trends and advises both established and startup financial technology companies.

Twitter: @AlexH_Johnson

LinkedIn: Linkedin.com/in/alexhjohnson/

I’ve purchased a home and refinanced it three times in the last three years. Yay low rates!

To be clear, Coolidge’s quote on the importance of home ownership is my favorite. As far as favorite presidents go, he’s solidly in the middle.

For much more analysis on the history and evolution of the U.S. mortgage market, I highly recommend checking out Marc Rubinstein’s newsletter — Financing the American Home. It’s an incredible read.

Over time, that 20-year loan term would stretch out to 30 years, which is the current industry standard.

Multiple financial crises, for a start.

MSRs are their own distinct asset class, separate from mortgage-backed securities. MSRs are valued based on an analysis of how likely borrowers are to make their payments and how long they are likely to be making those payments for. Prepayment (i.e. the customer paying down their loan early or refinancing) is an MSR owner’s worst scenario because it shortens the length of the loan and, thus, the amount of revenue an MSR owner can generate.

The rate at which mortgage securities and mortgage servicing rights are sold has increased so much in the last 40 years that it led to the creation of Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems (MERS), a privately held corporation that tracks mortgage ownership and servicing rights and has such a bonkers history that a Florida foreclosure lawyer once compared it to a “creature more akin to a many-tentacled squid.”