The Implications of Ownership

Asset ownership is becoming central to new models in financial services.

Editor’s note — at the end of today’s piece, you’ll notice that it’s missing my customary ‘short takes’ on recent news headlines. This is by design. I will be making some changes to the format of the newsletter over the coming weeks. If you have ideas or feedback on either its content or structure, now is the time to share them! Reply to this email or hit me up on Twitter and let me know what you’d like to see.

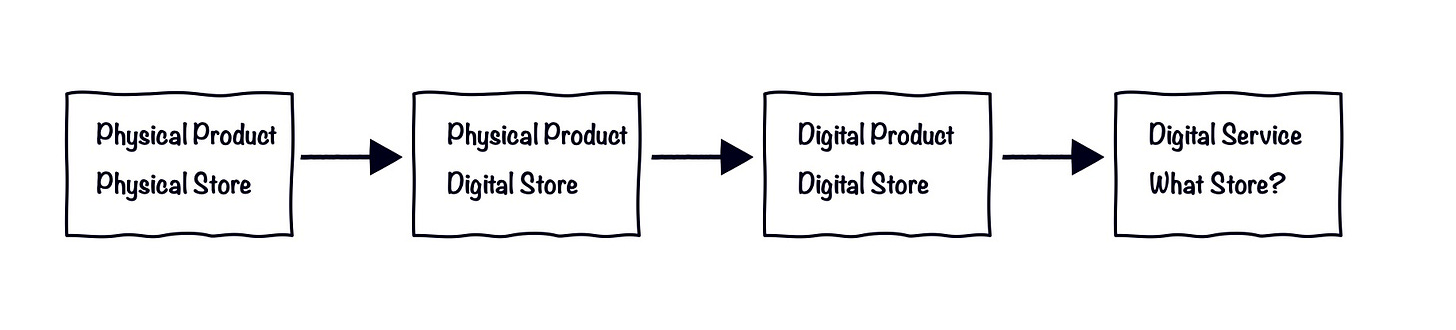

Here’s one way to think about the digitization of product manufacturing and distribution.

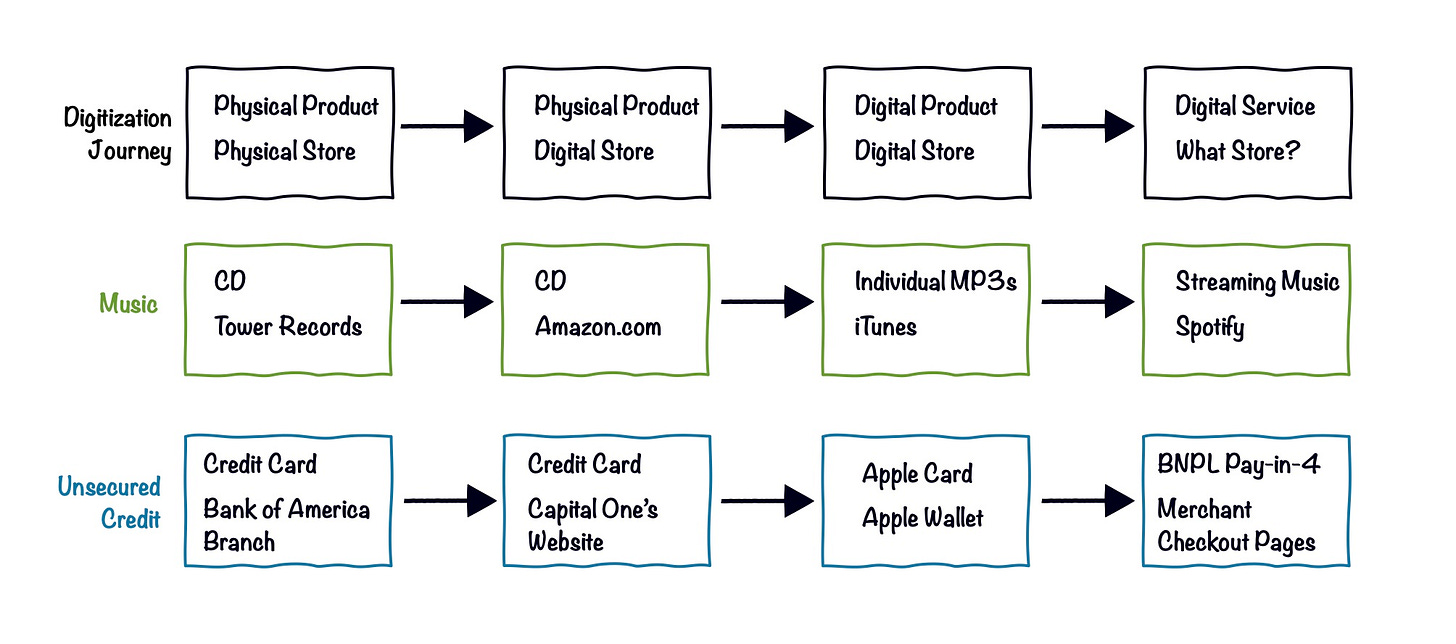

You start with a physical product — say a CD — sold through a physical store, like Tower Records. You then transition to that same physical product sold through a digital store; picture Amazon.com selling a CD. Then you move to a digital version of that product, sold through a digital store. This is where things start to get interesting, because the digitization of the product allows for the nature of the product itself to change in ways that wouldn’t have been possible before. In the case of music, this was the jump we made from physical albums to individual MP3s sold through digital music stores like iTunes. And finally comes streaming, in which consumers stop buying individual digital products and instead continuously consume an equivalent digital service. In this end state, the notion of a ‘store’ starts to fades away as consumers stop shopping and start subscribing. Think Spotify replacing iTunes as the dominant distribution channel for digital music.1

At a 30,000 foot level, the journey looks something like this:

This model has been a very popular way to frame the digitization of financial services over the last couple of decades.2 Take credit cards as an example.

You start with a physical credit card, acquired in a bank branch. Then you get digital account opening, which enables the acquisition of physical credit cards through online and mobile channels. Then you get virtual cards and instant issuance, whereby a consumer can apply on a mobile device and instantly get approved and have a digital version of the card provisioned to their mobile wallet. And finally you get streaming credit, where consumers gain on-demand access to unsecured loans, when and where they need them (rather than through a ‘store’). Using this lens, we can consider BNPL the evolutionary descendent of credit cards:

This mental model makes intuitive sense. It’s neat. Everything fits nicely into boxes. It’s linear and because it’s linear it feels inevitable. Some industries may be a little ahead and some (*cough* banking *cough*) may be a bit behind, but everyone is headed in the same general direction.

The trouble with this model is that it leaves out a couple very important concepts.

First, not all products can or should be digitized. Until Zuck has us all plugged into his metaverse 100% of the time, we’re going to continue to need new iPhones and cars and Oculus headsets, to say nothing of products that can technically be digitized but that some of us prefer to enjoy in their older physical forms.3

And it’s not just the products themselves. Physical products often require physical stores. There are certainly cases where this isn’t true, but there’s a reason that car dealerships still exist. People like to test drive new cars before they spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars on them. Thus, the car buying experience can be digitized in places, but it will never be fully removed from the world of atoms.

Second, and more importantly, the model described above fails to take into account the notion of ownership.

Let’s Talk About Ownership

Specifically, let’s talk about the following points:

Assets are Underutilized

One thing that distinguishes the ultra wealthy from everyone else is their ability to extract maximum value from the assets that they own. Elon Musk provides a topical example. After offering to buy Twitter for $43 billion, a lot of people asked where Mr. Musk was planning to come up with the money. It was a good question! For being the world’s richest human, Elon is strangely cash poor. The vast majority of his wealth is tied up in the Tesla and SpaceX stock that he owns. For the most part, this situation seems to suit him just fine. But, but! When he needs to come up with $43 billion real quick, because Twitter’s Board of Directors thinks he’s full of shit, what does he do? He borrows it! As was recently reported, Elon Musk has succeeded in lining up funding to buy Twitter by, among other things, taking out a personal loan of $12.5 billion, secured by $62.5 billion worth of his Tesla stock.

That’s incredible for a lot of reasons, but one of them is how starkly it contrasts with the way that most consumers fail to extract value from the assets that they own. Let’s use home ownership as our example. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, at the end of 2021, Americans had accumulated approximately $14 trillion worth of mortgage debt for the purchase of single and multifamily housing. Analysis from ATTOM, a property data analysis company, found that more than 40% of mortgage residential properties in the U.S. were considered equity-rich, which means that the combined estimated amount of loan balances secured by those properties was no more than 50% of their estimated market value.4 In other words, a large percentage of American homeowners have access to a massive financial asset.

And what are they doing with that asset? Nothing so excessively dramatic as buying Twitter certainly, but perhaps taking out home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) to help pay down credit card debt or fix up their homes or start up a small business?

Nope. According to analysis from ATTOM, U.S. consumers took out roughly $200 billion in HELOCs in 2021, a significant decrease from the prior year and a small portion of the total amount of equity controlled by American homeowners.

Why is this?

There are a lot of reasons, but one that stands out to me is the amount of work it takes to get a HELOC. Depending on the appraisal process and the documentation required, it can take anywhere from four to six weeks to close on a HELOC and up to another couple of weeks to access the funds.

Now, of course, it’s not exactly a simple process for Elon Musk to borrow $12.5 billion against his Tesla stock, but the difference is that he can pay people to handle that highly manual and time-intensive process for him and to expedite it as much as he needs. Most consumers don’t have that luxury. They need technology to automate it.

The Cost to Manage Asset Ownership has Decreased

Here’s some good news on the technology front — it has never been easier or less expensive to digitally track and manage asset ownership. For proof of this, one need only look at the emergence of fractional investing and the proliferation of alternative asset investment offerings, which, when taken together, have given every consumer the ability to efficiently amass a diversified portfolio of fine art, rare wines, and classic cars.

This would have been unfathomable to legacy technology companies in industries like mortgage servicing, which built arguably less complex ledgers at significantly greater expense.

Web3 Gives Us a New Way to Enable Control Over Assets

Sticking with the technology thread for a bit longer, we need to talk about Web3. Set aside all of the scams and the nonsense for a minute. The cool thing about the technology underpinning Web3 is that it has the potential to shift the way in which creators and consumers exercise control over the assets they interact with.

Simon Taylor (a tall human5 and writer of the wonderful Fintech Brainfood newsletter) shared a great framework for thinking about the changing nature of ownership. It has three parts: asset, access, and control.

Simon uses a house as a metaphor:

Asset: This is the house itself, an asset whose value is determined by characteristics like square footage and location.

Access: This is the key. It gives the holder the ability to enter and exit and to extend those privileges to others. Crucially, however, access doesn’t confer ownership.

Control: This is the deed to the property. It confers legal ownership, which in turn gives the holder of the deed control over the asset; to sell it or significantly alter it or leverage it for financial gain.

Now let’s use a different metaphor to demonstrate the potential value of Web3 — music.

Today, we have Spotify. It essentially acts as a marketplace, connecting artists with consumers and taking a cut of the value generated by transactions between the two. The asset is the music. Artists and consumers have a level of access (consumers can log in to access the service and change their preferences, artists can log in to upload music, drive discovery, and measure performance), but control is retained by Spotify. An artist can’t, for example, reward their 10 most frequent Spotify listeners with a small fraction of ownership in their favorite songs’ future revenue streams. The technology is simply not designed to allow for it (to say nothing of the business model).

In Web3, control over the asset can be retained by the wallet that created it. In this example, the artist could retain control over their music, allowing them to give ownership of the asset (or a fraction of it) to a loyal fan and allowing that fan to sell or leverage that asset however they see fit.

The Circular Economy is Coming

The final point I want to cover is a change in the way that consumers, particularly younger consumers, value the concept of ownership.

Let’s start with a definition. A circular economy is one in which resources are used for as long as possible and are then restored and repurposed when their use is over. In a circular economy, consumers value long-term ownership and the creative reuse of assets.

Why is this important?

Put simply, because Gen Z believes in it.

According to research complied by Twig (an interesting company that I’ll tell you more about in a bit) 43% of Gen Z shoppers actively look for brands and retailers that have environmental practices and 80-90% of Gen Z shoppers buy sustainably, either usually or sometimes.

This commitment to sustainability also shows up in the consumption choices that Gen Z consumers are making, according to a survey conducted by Gen Z-focused marketplace app Depop. They found that 90% of surveyed Depop users have made changes in order to be more sustainable in their daily lives, including reducing fashion consumption (70%), repairing clothing (60%), and only buying secondhand clothing (45%).

A New Model

A quick recap:

Consumers underutilize the assets that they own, however …

The cost to track and manage asset ownership has come down significantly in the last couple of decades, which has led to an increasing ability to democratize access to previously-unavailable asset classes. This is a significant shift, especially when you consider that …

Web3 has the potential to further empower creators and consumers to retain, transfer, and leverage ownership over assets, which is particularly interesting given that …

Gen Z is placing a greater emphasis on the importance of long-term ownership and the creative reuse of assets, driven by concerns about sustainability and the environment.

Due to these trends, I believe we need to toss out our old model for thinking about digitization and come up with a new one; one that puts asset ownership at its center:

You’ll notice that my new model is rather vague in its design. That’s intentional. I don’t think we know yet how exactly these new, ownership-centric models for manufacturing and distributing products are going to look. Nor do we know exactly how these new models will impact the ways in which consumers acquire and utilize financial products and services.

However, we do have a couple of hints.

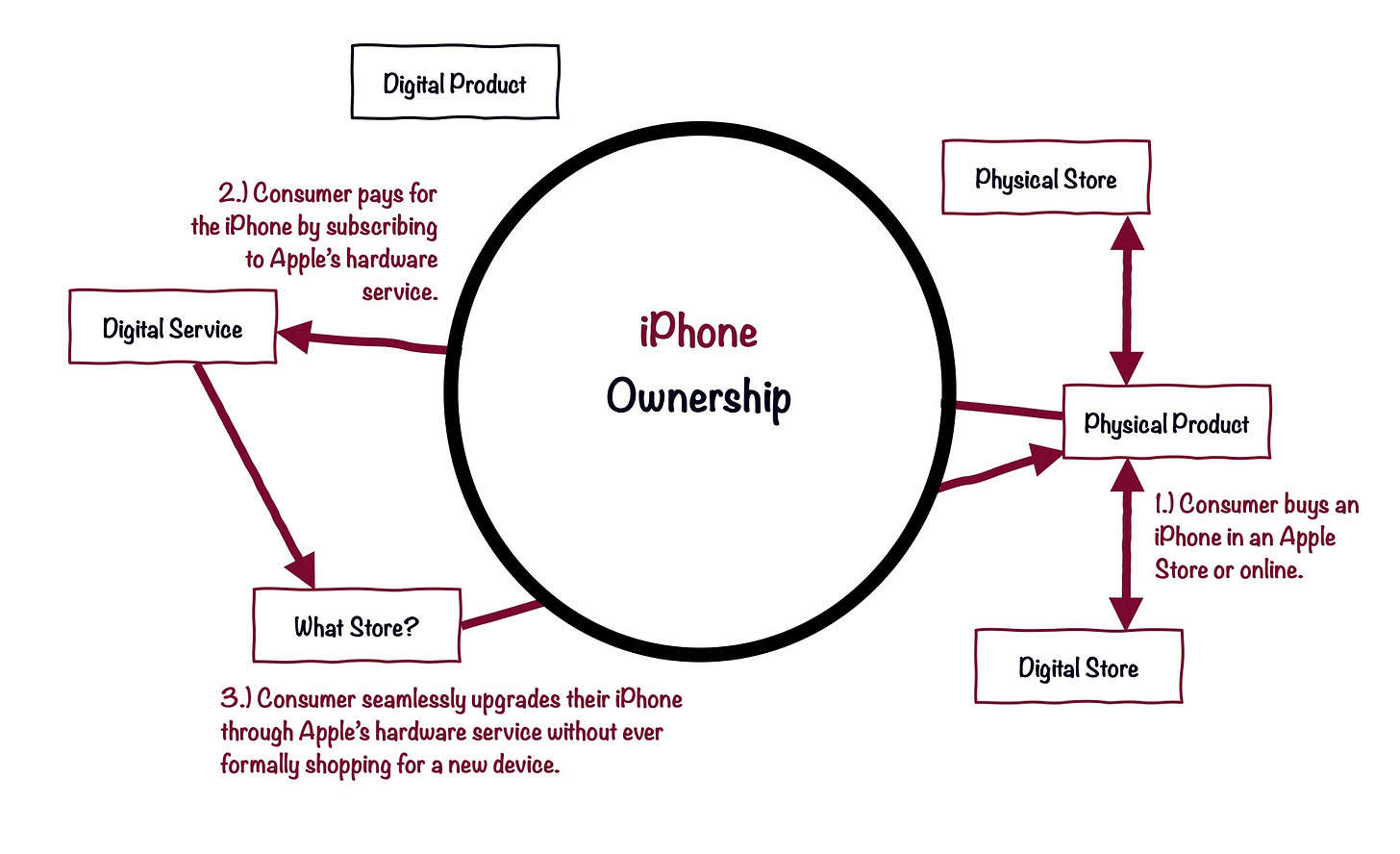

The first comes from Apple.

According to reporting from Bloomberg:

Apple Inc. is working on a subscription service for the iPhone and other hardware products, a move that could make device ownership similar to paying a monthly app fee

The idea is to make the process of buying an iPhone or iPad on par with paying for iCloud storage or an Apple Music subscription each month. Apple is planning to let customers subscribe to hardware with the same Apple ID and App Store account they use to buy apps and subscribe to services today.

The company has discussed allowing users of the program to swap out their devices for new models when fresh hardware comes out.

The subscriptions would likely be managed through a user’s Apple account on their devices, through the App Store and on the company’s website. It would likely also be an option at checkout on Apple’s online store and at its physical retail locations.

This service, when overlaid on top of our new, ownership-centric model, would look something like this:

It’s important to note that the success of this hardware subscription model will be highly dependent on Apple’s ability to seamlessly integrate financial services capabilities such as payments, lending, and risk underwriting into the service, which is reportedly one of the motivations driving Apple’s recent investments in bringing more financial services capabilities in house.

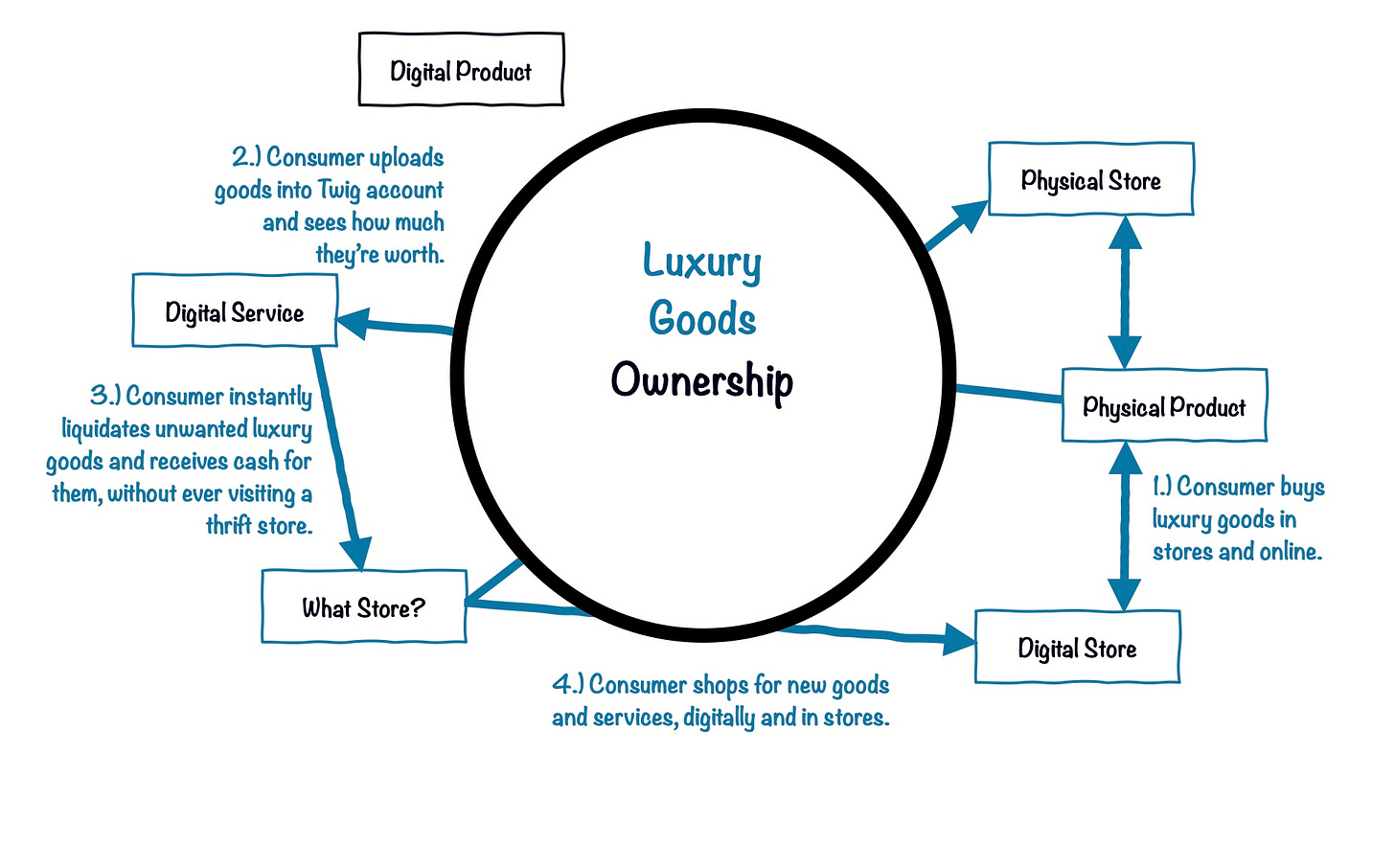

Our second hint comes from that company I promised to tell you more about — Twig.

Twig is a digital bank built on circular economy principles. It’s basically what you would get if Cash App and Aspiration had a baby and that baby was kidnapped at birth and raised by thredUP.

Here’s how it works:

You open up a Twig account and debit card, which provide the standard neobank spending and P2P payments functionality that you’d expect as well as impact analysis and carbon offsetting capabilities (à la Aspiration).

You upload a list of the luxury goods that you own (typically high-end clothing and electronics) and Twig uses its market-based pricing algorithm to instantly assign a value to each item.

Whenever you want, you can instantly sell any item that Twig has assigned a value to, for that exact amount, and receive an instant payment into your Twig account. You then mail the item (for free) to Twig, for them to resell or recycle.

Twig’s CEO boils down the pitch for his company to this — “we tokenize assets.” Here’s what that looks like, applied on top of our model:

Where Are We Going?

I don’t think it’s possible yet to predict if these new, ownership-centric models will gain meaningful traction with consumers, but it’s not hard to imagine how such models could significantly impact the financial services industry *if* they do.

This transition from discreet digital products to streaming digital services also unlocks new opportunities for product innovation. Sticking with music, a good example is Spotify’s public playlists, which are only feasible in an environment where all customers have access to the same massive music library.

Brett King was the first person who I heard use this framing to explain the changes that were happening in the financial services industry. As per usual, he was ahead of the curve.

I adore physical books and I will die on this hill.

This is one of the few silver linings to the out-of-control growth in house prices in the U.S.

Height was a topic of conversation at this week’s New York Fintech Week. I don’t really want to talk about it though.