Solving the Credit Invisibility Problem

Why building on-ramps to the U.S. credit system is harder than it seems.

If fintech has a superpower, it’s the ability to hone in on the most quietly frustrating parts of banking, the parts that consumers have mostly learned to live with, and build (and loudly promote) products that address those frustrations.

Here’s Chime CEO Chris Britt:

People have a lot of anxiety around their money and we think that starts with not charging you a fee on your checking account, and letting you go overdraft without charging you a $35 overdraft fees

And if they’re successful enough at drawing attention to these wedge issues and driving consumer adoption of their corresponding wedge products, they can force incumbents to respond:

“We know that money can be a source of stress and confusion,” said Diane Morais, president of consumer and commercial banking at Ally Bank, in a press release. “Overdraft fees can be a major cause of anxiety. It became clear to us that the best way to relieve that anxiety was to eliminate those fees.”

Overdraft fees were a logical place for U.S. challenger banks to challenge the status quo and the resulting traction that challenger banks have gotten on no-fee deposit accounts seems poised to lead to a race to the bottom for bank overdraft revenue, which will be enormously beneficial for consumers (if it happens).1

The question is what’s next? What is the next wedge issue that fintech startups can turn into a successful wedge product?

How about credit invisibility?

Credit Invisibility in the U.S.

Depending on who you ask, the number of U.S. consumers that are unable to access mainstream credit products is somewhere between 45 and 60 million.

According to research from the CFPB, these consumers fall into two main groups:

“Credit invisibles” are consumers who do not have a credit record with the NCRAs. … Another group consists of consumers who have limited credit records with the NCRAs, but the records are deemed “unscorable” because they (i) consist of stale accounts (i.e., no recently reported activity) or contain too few accounts or accounts that are too new to be reliably scored.

And, like everything else in this country, the burden of credit invisibility isn’t distributed equally. Here’s the CFPB again:

Credit invisibility and unscorable credit records affect some segments of the population more than others. About fifteen percent of Blacks and Hispanics are credit invisible compared to roughly 10 percent of Whites and Asians. Thirteen percent of Blacks and 12 percent of Hispanics have unscorable credit records compared to about 7 percent of Whites and close to 8 percent of Asians. In addition, young consumers are more likely to be credit invisible.

To understand why this is the case, it’s important to unpack, in more detail, how U.S. consumers gain access to the U.S. credit system.

In 2017, researchers at the CFPB conducted a study, looking at the de-identified credit records for over 1 million U.S. adults who made the transition from credit invisible to credit visible. The study documented the types of information that led to the creation of these consumers’ credit records and if and how these consumers were aided by family or friends in establishing those credit records.

Here is what they found:

A few quick observations:

The top three ‘on-ramps’ to the U.S. credit system aren’t a surprise. Giving credit to someone who has never had credit is easiest when the risk is: A.) owned by someone else (student lending, 92% of which is underwritten by the U.S. Government), B.) subsidized by a third-party with a vested interest (retail loans, which seem likely to increase as merchant adoption of BNPL increases), or C.) balanced out by the potential for enormous profits (credit cards).

And speaking of credit cards, according to the CFPB less than 1% of consumers younger than 25 used a secured credit card as their entry point to the U.S. credit system. This isn’t a surprise given that secured cards are far less profitable for banks than unsecured cards.

Collections as an entry point into the U.S. credit system — in which a consumer’s first credit record captured by the credit bureaus is an unpaid financial obligation (most frequently an unpaid medical bills or debts for cable or cellular service) — is an unambiguously bad thing. It sets these consumers at a disadvantage immediately as collections notices are among the most damaging credit characteristics in most lenders’ underwriting models.

This is especially concerning when you dig deeper into the data and discover that lower income consumers are much more likely to start their credit journey with collections:

In low-income neighborhoods, 27.1 percent percent of consumers have credit records created from these non-loan experiences. In contrast, non-loans are the entry products for only 8 percent of consumers in upper income neighborhoods. This means that consumers in low-income neighborhoods are 3 times as likely to acquire their credit history from a non-loan. Since these experiences are generally treated as derogatory events, this suggests that consumers in lower-income neighborhoods are more likely to start their credit records with unfavorable items.

Another disadvantage for consumers from low-income neighborhoods is that they have fewer opportunities to acquire joint accounts or become an authorized user on established credit account, both of which represent safer ways to establish credit histories:

24.5 percent of consumers transitioned out of credit invisibility by relying in whole or in part on the creditworthiness of others. Notably, this percentage was significantly lower for consumers in low-income neighborhoods, where 14.9 percent relied on the creditworthiness of others, than it was for consumers in upper-income neighborhoods (30.3 percent).

Given that credit is an essential tool for building financial health and resiliency and given that the current on-ramps to the U.S. credit system are, in a number of ways, deeply flawed, it’s understandable why fintech companies would be interested in making the problem of credit invisibility a priority in their product roadmaps.

The challenge is that, unlike overdraft fees, it’s surprisingly difficult to build a good wedge product around the problem of credit invisibility.

The Problem with Credit Builder Products

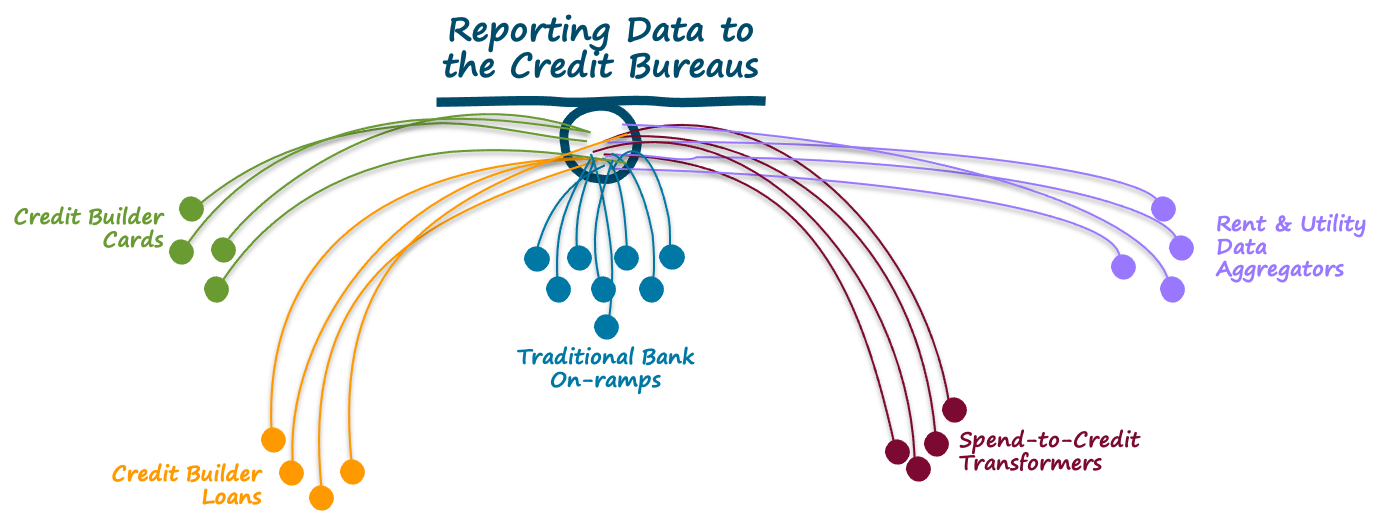

The most common fintech solution in this space is credit builder products. As the name suggests, these are financial products that are designed to help consumers establish and develop positive credit histories. They come in many different flavors, but they are all essentially designed to do the same thing — generate positive repayment data that can be reported back the the three credit bureaus.

The thinking behind credit builder products looks something like this:

Banks have failed to create safe, low-cost on-ramps to the U.S. credit system.

Most consumer credit in the U.S. is provided by banks.

Banks rely primarily on the credit bureaus and the FICO score to make credit decisions.

So let’s build a new product that makes it drop-dead simple for consumers to generate and report positive data to the credit bureaus and improve their FICO scores.

The theory makes sense.

In practice, however, it’s really difficult to build a product that is both novel and appealing to consumers and effective at responsibly improving consumers’ credit scores. It’s a bit like shooting a basketball; the farther away from the hoop you get, the more your shooting percentage decreases.

Let’s run through a few examples:

Credit Builder Cards

What are they?

A clever twist on secured credit cards.

These cards — offered by fintech companies like Chime, Varo, cred.ai, and Step — automatically set aside money from a linked deposit account as they are used, ensuring that customers always have the money to pay their bill at the end of the month and, for all practical purposes, eliminating the risk of default. When the bill is paid, the card provider reports the repayment to the bureaus.

These cards typically come with no interest and few fees (primarily generating revenue for the providers through interchange).

What’s the problem?

Bureau-based credit scores help lenders assess borrowers’ character, which is credit underwriter speak for willingness to repay debt. This type of credit worthiness assessment is especially useful for long-term credit obligations (auto loans, HELOCs, mortgages) and for lending across different macroeconomic conditions (a person’s willingness to repay debt tends to be fairly stable).

Credit builder cards are great for consumers, but the concern is that the repayment data that they are generating and reporting to the bureaus (which is almost guaranteed to be positive) isn’t the most reliable signal for those customers’ willingness to repay future debts.

Credit Builder Loans

What are they?

Installment loans that don’t fully pay out until after the customer has already paid them off.

Offered by fintech companies such as Self, SeedFi, and MoneyLion, these products are essentially reverse loans. A consumer makes monthly payments (which are a combination of the principle and interest) until the full amount of the loan (typically between $500 and $1,000) is paid off and then the money (minus interest and fees) is released to the customer (some products pay a portion of the loan out upfront). This reverse structure protects the lender, in case the customer doesn’t make all their payments.

Over the course of the loan term, the customer’s payments (or missed payments) are reported to the credit bureaus.

What’s the problem?

To put it mildly, credit builder loans are not great for consumers. They are marketed as products that allow you to “save money while building your credit”, but the costs of the loan (fees and interest) far outstrip the yield that customers get on their “savings”, which makes it an expensive option for establishing and building a credit history.

Check out this Twitter thread for all the gory details on MoneyLion’s credit builder loan:

Spend-to-Credit Transformers

What are they?

Lines of credit or installment loans that allow consumers to pay for stuff that they are already buying, thus establishing and/or building their credit histories.

They essentially transform existing spend into credit transactions that can be used to build consumers’ credit histories.

There are two flavors.

The first are revolving lines of credit that are designed to be linked to a debit card, provided by fintech companies like Extra and Grain. When a customer uses their debit card, the revolving line of credit is used to cover the purchase and is automatically repaid by the debit card. These lines of credit come with fees and, in the case of Grain, an interest rate.

The second type of offering is a fixed installment loan tied to specific recurring transactions. An example of a provider in this space is Grow Credit, which offers 12-month installment loans, accessed through a virtual Mastercard, which can only be used to pay for recurring subscription payments like Spotify and Disney+. Grow Credit uses a freemium model, offering small loans ($17 per month) for free and bigger loans (with the ability to pay for more types of subscriptions) for a monthly fee.

What’s the problem?

It’s a little bit of the worst of both worlds.

Like credit builder loans, they’re expensive. They offer little to no value unless consumers are willing to pay fees and possibly interest.

Like credit builder cards, they’re not providing the greatest ‘willingness to pay’ signal back to the credit bureaus. Automatically linking credit lines to debit cards takes the control to make repayment decisions out of the customers’ hands. Giving small dollar loans to pay for services that customers are already paying for and are highly unlikely to default on doesn’t tell lenders anything about their willingness to prioritize debt repayment.

Rent & Utility Data Aggregators

What are they?

Services — provided by companies like Experian, LevelCredit, and Perch — that confirm, collect, and furnish data to the credit bureaus on how consumers are paying their utilities (everything from electricity and internet service to Netflix) and rent.

These services are monetized in a variety of ways, with some providers opting to directly charge customers a fee (LevelCredit costs customers $6.95/month) and some generating revenue through B2B relationships (Boost is free for consumers, but generate revenue for Experian through lead referrals).

What’s the problem?

Reporting new data to the credit bureaus sounds lovely, but it only makes a difference if that data is taken into account by the credit scores and proprietary underwriting models that lenders use to make credit decisions.

In the case of rent data, only FICO 9 (and FICO 10) take rent data into account. Unfortunately, most lenders haven’t adopted FICO 9 yet and we are likely years (perhaps decades) away from a majority of lenders taking that step.

Utility data is more widely used in commercial scores (FICO 8 takes it into consideration and is used widely in most consumer lending decisions), but even a long history of positive utility payments can only offer a modest bump in a consumer’s credit score (which lenders may still discount in their own proprietary underwriting models).

Make The Hoop bigger

The most successful fintech companies, your Chimes and Cash Apps, are product development machines. You feed in customer problems/frustrations/annoyances and the machine spits out new products and product features to address them.

Credit invisibility is the rare banking problem that breaks this machine. The constraints of the problem — build me a differentiated solution that doesn’t require our customers to do anything different from what they’re already doing but will produce reliable willingness to pay signals that the credit bureaus will accept and that the credit scores already in commercial use will take advantage of — are simply too onerous to allow for the elegant solutions that fintech product designers prefer to create.

In order to start making meaningful traction on solving the credit invisibility challenge, fintech companies need to enable banks and other fintech companies to change the constraints of the problem. To return to the basketball analogy used above, we need to shift our focus away from making difficult shots and towards making the hoop itself bigger.

Start with first principles. Identify the specific segments of consumers that struggle with access to credit — young adults, recent immigrants, military veterans, and even older consumers who have stopped using credit and have seen their credit histories dissipate. Think deeply about the structural challenges in lending responsibly to these groups and focus on building the infrastructure necessary to address those structural challenges.

This approach isn’t easy. It doesn’t fit neatly into a two-week product development sprint. It takes patience and significant upfront investment, but the impact on both the fintech company itself and the broader industry (over time) can be significant.

Here are two examples that are starting to show promise:

Building an international credit reporting infrastructure. Recent immigrants represent roughly one fifth of the credit invisible population in the U.S. and 70% of those immigrants come to the U.S. from a small number of countries (about two dozen) that have mature credit reporting infrastructures in place.2 This tees up an obvious question — why isn’t there a mechanism for U.S. lenders to acquire, transform, and utilize credit bureau data from other countries in order to approve recent immigrants for credit? Nova Credit, a credit reporting agency founded in 2015, was created to do just that. With the consent of the consumer, Nova Credit can acquire credit files from the countries that U.S. immigrants are emigrating from and normalize that data so that U.S. lenders can easily leverage it for automated credit underwriting.

And while it took a lot of time to build the infrastructure necessary to do this, Nova Credit is starting to see significant traction with U.S. lenders like American Express embedding Nova Credit’s ‘credit passport’ capabilities directly into their digital account opening processes.

Democratizing access to cash flow-based underwriting. In contrast to credit bureau-based underwriting, which facilitates an evaluation of a borrower’s character or willingness to repay debt; cash flow-based underwriting uses bank transaction data to assess a borrower’s capacity or ability to repay debt. This approach to credit evaluation works well for shorter-term and smaller-dollar loans and, unlike traditional credit scores, it don’t require lengthy credit histories. Cash flow-based underwriting is all about recency — do you currently have the capacity to repay this loan? — which means that it can operate on as little as 3 months of bank transaction data. And while it isn’t, by any means, a new concept in lending, the emergence of open banking (enabled by infrastructure providers like Plaid and MX) has made automated, real-time cash flow-based underwriting much easier to enable. Fintech companies like Petal, founded in 2016, have built robust consumer lending businesses using cash flow data to underwrite consumers with thin or no traditional credit histories (70% of Petal’s roughly 100,000 credit card customers had thin or no credit files at the time they were originated).3

Petal’s direct success in the market using cash flow-based underwriting led to the company recently productizing its proprietary CashScore and making it available via an API for banks and other fintech companies to incorporate into their underwriting processes.

Additionally, the growing awareness and acceptance of cash flow-based underwriting and the public pressure that fintech companies have put on banks to help solve the credit invisibility problem have (reportedly) pushed the biggest banks in the U.S. to an unusual level of cooperation around the use of deposit transaction data to approve credit invisible consumers for credit cards:

JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, U.S. Bancorp and others will factor in information from applicants’ checking or savings accounts at other financial institutions to increase their chances of being approved for credit cards, according to people familiar with the matter. The pilot program is expected to launch this year.

It is aimed at individuals who don’t have credit scores but who are financially responsible. The banks would consider applicants’ account balances over time and their overdraft histories, the people said.

Short Takes

(Sourced from an incredible fintech news ecosystem)

For Whom?

U.S. Bank launched video banking for customers.

Short take: Do consumers really want to interact, over video, with human bankers? Maybe, but it’s hard not to see this new set of features as a way for U.S. Bank to justify its current branch staffing costs.

Let’s Be Clear

Lemonade posted some questionable Tweets about its automated claims processing.

Short take: Many fintech companies can’t resist the temptation to brag about their technological superiority over incumbents and this occasionally provides a glimpse into the disturbing ways that technology is being used.

Investing in Underserved Communities

PayPal invested $135 million into credit unions serving black and underserved communities as part of its $535 million commitment to racial equity.

Short take: Investing in racial equity by investing in mission-driven credit unions is a fascinating acknowledgement of the important role that community-based financial institutions play in the lives of underserved consumers.

Featured Research

Fintech Fire Alarms is a monthly summary of the five trends in fintech that should be impacting bank and fintech companies’ strategic thinking and product roadmaps. Check out the Fintech Fire Alarms for May, 2021 and subscribe so that you don’t miss any in the future!

Alex Johnson is a Director of Fintech Research at Cornerstone Advisors, where he publishes commissioned research reports on fintech trends and advises both established and startup financial technology companies.

Twitter: @AlexH_Johnson

LinkedIn: Linkedin.com/in/alexhjohnson/

A word of caution here: Ally was really well positioned to eliminate overdraft fees as they weren’t making a ton of revenue on them anyway and they don’t have the same branch-heavy cost structure of other banks that might need overdraft fee revenue to prop up profitability.

Trivia question: what is the only G20 country without a traditional credit bureau?

Answer: France

Check out this independent study by the FinRegLab on the efficacy of cash flow-based underwriting.