The Product Developer's Dilemma

The consequences of democratizing access to financial services.

Let’s start with a contradiction.

A commonly-accepted tenet of crypto investing for beginners is to operate over long time horizons. Given the inherent volatility of cryptocurrencies, structured investment strategies that require patience tend to perform better for new investors who lack the knowledge, time, and capital to day trade effectively.1 Here’s Coindesk explaining an investment strategy called Dollar Cost Averaging:

Buying at regular intervals like this over a long period of time helps to reduce the impact of market volatility – when prices rise and fall sharply – and means, on average, Bob will likely get more bitcoin for his money than if he had spent all his money at once.

In the HODL worldview, selling should be a strategic decision aligned with your long-term financial goals (retirement, asset diversification, etc.) and done in accordance with an overall strategy for minimizing capital gains taxes. You should never sell your cryptocurrencies for impulsive reasons like, for example, buying a new pair of cowboy boots.2

And yet, PayPal is empowering its customers to do just that:

PayPal’s move is significant, as it marks the first time average consumers … will be able to spin cryptocurrency into spending power at a large array of merchants. … The crypto option is now available for use with more than half of PayPal’s 29 million U.S. merchants, with more on their way.

This capability is enabled by PayPal’s clearinghouse partner, Paxos, which (like most crypto infrastructure companies) was founded by folks that strongly believe in cryptocurrencies’ potential as a long-term store of value:

Paxos and other crypto infrastructure companies have been so successful at stripping out costs and abstracting away complexity from the process of buying and selling cryptocurrencies that they are now enabling use cases that are literally the opposite the HODL rallying cry that their industry is built on.

How did we get here?

Democratizing Access to Financial Services: A Story, in Two Parts

Fintech is lauded for democratizing access to financial services.

These plaudits are often well deserved.

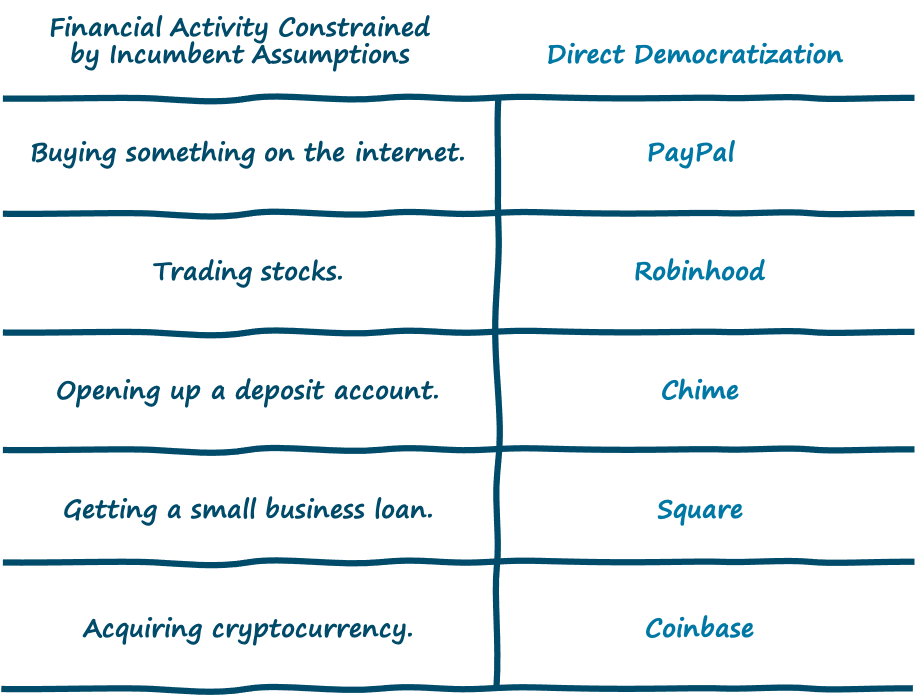

Banks are built on assumptions; assumptions about which customers they can profitably serve and which use cases they can efficiently solve for. These assumptions have always left some customers and some use cases on the outside looking in:

I want to open up a bank account without going to a branch.

I want to safely make payments over the internet.

I want to trade stocks without having to speak to my broker on the phone.

I want to get an affordable small business loan in less than six weeks.

This dynamic isn’t unique to banks. Assumptions (and the legacy thinking that tends to calcify around them) quickly form in even the newest and most innovative corners of the market. After all, it wasn’t that long ago that industry observers were assuming most people wouldn’t own cryptocurrencies because they were too complicated to understand and too difficult to use.

And yet, today most of us can quickly, easily, and affordably open a deposit account, buy or sell stocks and cryptocurrencies, acquire a small business loan, and safely pay for a whole big bunch of stuff over the internet.

Technology tends to render the assumptions of market incumbents obsolete, to the benefit of disruptors like PayPal, Square, Robinhood, Chime, and Coinbase, which have directly democratized access to financial products and services that banks couldn’t or wouldn’t provide at scale.

When people talk about how fintech is democratizing access to financial services this is typically the type of thing they’re referring to.

But it doesn’t stop there.

Success attracts fast followers. The growth of PayPal (read: eBay) fueled a booming interest among entrepreneurs in e-commerce.

Unfortunately, the technology built by PayPal to facilitate the direct democratization of electronic payments wasn’t well-suited for enabling other companies to follow in its footsteps:

Paypal – designed to simplify payments – actually made this worse. The company infuriated startups with its restrictions – once turnover hit a certain level, Paypal automatically put the business on a 21 to 60 day rolling reserve, meaning that up to 30 per cent of a company’s revenue could be locked up for up to two months. Developers had to choose between this and complex legacy systems built by banks.

Enter Patrick and John Collison, the founders of Stipe, who were so convinced of the need for a better solution for enabling e-commerce that they actually pitched it to the founders of PayPal:

In 2011, they approached Peter Thiel and Elon Musk.

“It’s a little impetuous to go to PayPal founders and say payments on the internet are totally broken,” says John ... “But look, you can WhatsApp anyone around the world and it’s free. It’s a remarkable act of co-ordination between the telcos and ISPs and the people who own the fibre underneath the sea to create this global communications network. Then, if you look at the economic infrastructure, we haven’t even started.”

The two brothers pitched a vision of more internet commerce, driven by more connectivity and it being easy to use. “That had been the original vision of PayPal, but they hadn’t actually made it happen, so I think they got us, in a way that a lot of people didn’t,” John says.

Which is exactly what they built:

if you’re a developer building the next Kickstarter, or the next Lyft, and you have a two-person team, both of you writing relatively complex code and solving complex infrastructural problem, you need a simple payments API that – once installed – doesn’t keep changing.

Byrne Hobart’s recent newsletter on Stripe describes the development of these APIs as part of a larger trend — the creation of reliable ‘solid state’ software functions that can be quickly assembled by developers in increasingly complex configurations:

This is how software eats the world: by taking business functions one at a time, turning them into well-documented API calls with useful error messages (but infrequent errors) that can be chained together with arbitrary complexity and then run with minimal human involvement.

And what Stripe (and others) are doing for payments, companies like Alpaca, Bond, and Paxos (and many others) are doing for the rest of the financial software stack.3

This newer generation of companies aren’t serving customers directly. They are democratizing access to financial services functionality for product developers.

And while this ‘indirect democratization’ doesn’t get nearly the amount of discussion and analysis as its direct cousin, it’s incredibly important for understanding the future of financial product design.

The Product Developer’s Dilemma

Financial services, like most industries, struggles with a collective action problem.

It’s in the best interests of all financial services providers for consumers to be as financially healthy as possible — people with low levels of debt can afford to take out more loans, those with ample deposits can afford to spend more, etc. — and yet individual financial services providers are often incentivized to drive their customers to financially unhealthy choices. And the success of individual providers acting in their own best interests encourages others to do the same, regardless of the impact it has on the larger ecosystem.

There are numerous examples of this collective action problem negatively influencing banks’ product design choices4 — overdraft "protection" and credit card benefits designed to encourage breakage are two of my least favorite examples.

These examples are harder to spot in fintech because consumer-facing fintech companies have different priorities than banks. Instead of short-term profitability, most fintech companies are focused on growing their monthly active users, improving retention rates, and driving down customer acquisition costs.

Square’s Cash App is a good example. With 36 million monthly transacting active customers and an average customer acquisition cost of less than $5, Cash App is the envy of the U.S. neobank market.

A key to the Cash App’s success is engagement — continually finding ways to increase the amount of time that customers spend in the app. The more engaged a customer is, the more opportunities Square has to cross-sell additional revenue-generating services, which leads to lower customer acquisition costs and improved retention.

This means that the Cash App product development team is constantly searching for new ways to attract and keep consumers’ attention.

It’s not surprising then that the Cash App was way ahead of the curve on crypto, enabling customers to buy and sell Bitcoin as far back as 2017.

And while Bitcoin doesn’t generate much standalone profit for the Cash App, it has done wonders for engagement:

Bitcoin has helped increase gross profit per active customer and engagement in our broader ecosystem as bitcoin actives use other products, such as Cash Card and direct deposit, more frequently compared to the average Cash App customer.

Square’s success in leveraging Bitcoin as a mechanism to increase engagement within the Cash App ecosystem has encouraged PayPal to go even further, enabling (through Paxos) its customers to buy, sell, and pay for things with Bitcoin, Ethereum, Litecoin, and Bitcoin Cash.

At an individual level, you can understand PayPal’s thinking here — crypto worked for Square. We want to build a financial super app. Let’s double down.

And, so far, PayPal’s crypto bet seems to be paying off, according to an April 2021 interview with PayPal CEO Dan Schulman:

Demand on the crypto side has been multiple-fold to what we initially expected. There’s a lot of excitement.

But at a collective level, is this really the future that we want? Banking and fintech apps competing with each other for our attention by layering in the most compulsively engaging financial services functionality, regardless of the impact on our financial (and emotional) wellbeing?

Are we really supposed to believe that PayPal thinks that it is in its customers’ best interests to use cryptocurrencies to pay for things? Here’s Mr. Schulman again, answering a question from the same April interview on why they finally decided to introduce a consumer crypto service (emphasis mine):

We’ve been looking at digital forms of currency and DLT for six years or so. But I thought it was early, and I thought the cryptocurrencies at the time were much more assets than they were currency. They were too volatile to be a viable currency. And it was still a little bit too much of people not really understanding what they were going to get into

I think a more honest answer would have been “it’s still highly volatile and making payments with it is silly, but it’s great for increasing daily active users.”

This is what happens when you democratize access to financial services functionality for fintech product developers who are incentivized, in many cases, to increase customer engagement at all costs.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Today’s fintech product developers have access to an expansive toolbox. Composable financial services functionality can be combined in a virtually unlimited number of ways and that combined functionality can be embedded in virtually any product or experience. As Kevin Garnett might say:

This freedom needs to be paired with a more rigorous process for evaluating the impact that new features and functionality might have on the overall wellbeing of the customers using them. Engagement cannot be the only metric by which we measure success.

We need to apply a lot more scrutiny.

Does it make sense to combine crypto and self-driving money? Crypto and car insurance? Crypto and savings accounts? Crypto and piggybanks? Which altcoins should a neobank customer be able to buy? Should we be automating the process of gambling our spare change? Exactly how diversified should our retirement portfolios be? Should options trading and direct deposits from your employer live in the same app? How do NFTs fit in? What about the fractional ownership of physical assets like the Declaration of Independence?

These are the types of questions that fintech product developers should be wrestling with.

Sponsored Content

Only 5 days left to get your ticket to Fintech Meetup! Join 2,000+ participants from 950+ organizations — 500+ Startups, 400+ Banks & Credit Unions, 400+ Established Fintechs & Tech Cos., 100+ Investors and many more have already signed up — don’t miss out on joining them at the event that is revolutionizing Fintech networking! GET TICKET NOW!

Short Takes

(Sourced from an incredible fintech news ecosystem)

Democratization Don’t Stop

Robinhood is giving its customers direct IPO access.

Short take: Speaking of democratizing access to financial services, investing at the IPO stage seems to be the latest innovation. It’ll be interesting to see how long it takes to trickle down to the infrastructure layer.

A Big Amount

Amount, a white-label digital account opening provider for banks, raised a $99 million Series D at a $1 billion valuation.

Short take: BNPL is a good example of how fintech is putting pressure on banks to change, which drives a growing preference for fintech vendors (like Amount) over legacy tech vendors.

Corporate Card Craze

Business banking platform Rho launched its own corporate card.

Short take: It’s been fascinating to watch the corporate card space go from boring to red hot. Brex, Ramp, and now Rho. How many more corporate cards can the market support?

Featured Research

OK, this isn’t research per se, but I wanted to share a really cool new thing that Nik Milanović and Simon Taylor organized — The Fintech Nerd Collective, a group of passionately geeky fintech enthusiasts getting together once a month to answer a pressing question about fintech. Our inaugural question was — If you could build your own Neobank, what would be your first product and why?

Alex Johnson is a Director of Fintech Research at Cornerstone Advisors, where he publishes commissioned research reports on fintech trends and advises both established and startup financial technology companies.

Twitter: @AlexH_Johnson

LinkedIn: Linkedin.com/in/alexhjohnson/

Given recent events, I’m not convinced anyone can effectively day trade in cryptocurrencies, but I digress.

Imagine buying a pair of cowboy boots for $300 with Bitcoin, having to pay capital gains taxes on that transaction, and then finding out the next day that the $300 that you spent would now be worth $350 because Elon Musk tweeted that he’s setting up a solar-powered Bitcoin mining operation on the moon.

I realize Stripe is listed in this graphic twice. There’s a reason they’re the example that everyone defaults to for excellence in building APIs.

According to the Financial Health Network, financially vulnerable and coping households account for 84% of spending on fees and interest for financial services.