Fintech Enters the Era of Distribution

And the choice facing founders is this — Convenience or Community?

Building a successful fintech company (or any company, really) comes down to manufacturing and distribution. Can you build a compelling product that people want and can you distribute that product reliably and efficiently?

Manufacturing and distribution. These are the two challenges that every founder wrestles with.

The question that’s interesting to me is which challenge do you start with?

Obviously the answer depends on a number of specific factors — the customer problem that is being solved, the founding team and their very particular set of skills, etc. — but I also think it depends on the ‘era’ in which the company is being founded.

In financial services, I would argue that, after 15 years or so, we are leaving the era of manufacturing and entering the era of distribution.

The Manufacturing Era

The recent history of disruption in financial services can be hung on a timeline of product innovation.

Picture the first couple generations of neobanks incorporating budgeting capabilities, automated savings, early access to direct deposits, and fee-free overdraft into checking accounts. Or online lenders digitizing the entire customer journey, from acquisition and underwriting through servicing and collections.

The details don’t really matter for our purposes, it’s the pattern that matters — carefully pick a customer problem that is being solved sub-optimally by incumbents, build a significantly better alternative, and use the obvious appeal of that wedge product or experience to gain traction in the market.

This is the great unbundling of financial services, which we’ve been writing about for a while now.

(The infamous CB Insights ‘fintech unbundling banking’ graphic would normally be placed here, but I’ll spare you this time)

The crucial point with these companies is that they had to prioritize manufacturing over distribution because the products and experiences they wanted to offer didn’t exist. There was nothing off the shelf that they could use to get started. In a lot of cases, the things they wanted to do were considered impossible by regulators and bank executives. To prove it was possible, they had to manufacture it.

It’s not an accident that many of these ‘manufacturing era’ companies ended up spinning off fintech infrastructure companies to resell the technology they built in house or having ex-employees start fintech infrastructure companies to solve the problems they dealt with in house.

And it shouldn’t surprise us that many of these companies (though not all) relied on relatively conventional distribution strategies. After all, they manufactured a really compelling product! A product that hadn’t existed before. A product that, when presented through popular advertising channels like Google and Facebook, would essentially sell itself.

So, for the most part, that’s exactly what they did.

The End of the Manufacturing Era

The success of fintech over the last 15 years has, ironically, created conditions that have made it much more difficult for new fintech companies to succeed using the ‘manufacturing-first’ strategy of their predecessors.

First, and most importantly, fintech has become the single favorite category of VC investors (and, I presume, their LPs). In 2021, private companies raised a record $621 billion in venture funding globally. One out of every five of those venture capital dollars was invested in fintech.

That’s an absolutely staggering amount of money and the downstream effects of all that money being introduced into the ecosystem are profound.

Facebook and Google are the obvious winners. More money in fintech leads to more competition, which in turn leads to increased spending on digital advertising, which has produced the astronomical customer acquisition costs that today’s fintech founders are saddled with.

More fundamentally, this increase in competition has created significant pressure for new fintech startups to move fast.

Gone are the days when you had to spend years building your tech stack, negotiating partnerships, and perfecting your product. With the benefit of modern infrastructure and a mature BaaS landscape, you can build a new fintech company in months:

The trouble is that now that these fintech infrastructure companies exist, it has become really hard to justify not using them.1 This is obviously good for them (pick-and-shovel business baby!), but it can make it hard to manufacture a differentiated product with strong unit economics when you and all of your competitors are using (and paying for) the same couple dozen APIs.

And that challenge — building a differentiated consumer fintech offering — is compounded when you realize that your competitors are going to rapidly and continuously copy all of your cleverest and most unique product features, which forces you to do the same or risk falling behind.

The end result is a convergence of fintech product roadmaps, as I noted recently:

If you’re a well-funded BNPL company, you’re probably going to partner with e-commerce infrastructure companies and add banking and crypto capabilities to your app. If you’re a neobank, you’re likely going to add crypto and BNPL. If you’re building finance solutions for corporate customers, you will be tempted to converge towards a combination of AP/AR automation, corporate cards, and revenue-based financing in your product roadmap.

And this is where we find ourselves — in an intensely competitive environment in which it has simultaneously never been easier to launch a consumer fintech product and never been harder to launch a sustainably differentiated consumer fintech product.

So, what’s a clever fintech founder to do?

The Distribution Era

You could, of course, buck the fintech infrastructure trend altogether, take your time, and try to build a differentiated consumer fintech product from scratch. There are plenty unmet financial needs that require solutions fundamentally different than the financial products we have today. If you have unusually patient early investors and access to an abundance of spare engineering talent, you could conceivably go down this path.

Or, alternatively, you could shift the focus of your strategy for achieving competitive differentiation away from manufacturing and on to distribution.

This is the path I think we will see a majority of consumer fintech companies take over the next 10-15 years.

In fact, we already are.

Welcome to the era of distribution.

Two Horses

Let’s start with the obvious. If you’re going to pursue a differentiated distribution strategy, you can’t utilize the same tactics that everyone else is already using. No matter how clever you are in your execution, you can’t rely on social media advertising or leads from NerdWallet or generic influencer marketing or getting someone famous on your cap table and putting their name in the first paragraph of every one of your press releases. And if you say “SEO”, I’ll whack you with something heavy.2

Differentiated distribution strategies are differentiated precisely because they aren’t obvious or push-button easy. They are difficult to conceptualize and time consuming to execute. And because of that, they require focus. You can’t, as we say in Montana, ride two horses with one ass. You have to choose.

And that choice, from my perspective comes down to this — convenience or community?

Convenience

The argument for convenience, as the foundation of your differentiated distribution strategy, is that the acquisition of financial products is almost never the end goal of consumers:

Whether they’re willing to admit it or not, banks sell enabling products. Consumers don’t want mortgages and credit cards and 401Ks; they want a nice place to live, the ability to buy stuff (including stuff they can’t quite afford), and to not work until they keel over and die.

And, therefore, the most valuable thing you can do for your customers is to reduce the work necessary to get a financial product down to the absolute minimal level.

In this model, the details of the financial product itself are mostly irrelevant (as long as it can enable the outcome the customer is looking for). The important part is making the acquisition experience easy.

Take lending as an example.

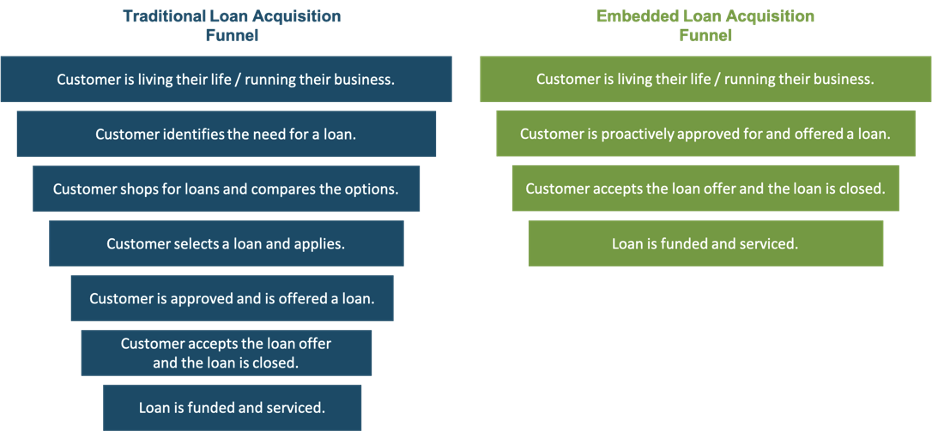

Traditionally, customers have had to identify the need for a loan, shop for providers, compare the product options, and apply for the one(s) that they prefer. The onus for acquiring the product fell, primarily, on them and banks competed in the shopping and product comparison stage and in making the remaining steps in the process as streamlined for the customer as possible.3

However, the ideal experience for customers isn’t a more convenient account opening process. It’s not having to apply for the loan at all. It’s embedding lending within the context of the activity that the customer is attempting to complete.

If the foundation of your differentiated distribution strategy is convenience, then the endgame that you are playing towards (whether you know it or not) is embedded finance.

The goal is to unobtrusively provide the needed financial services within the products and services that your customers already use to complete non-financial services activities. Think of auto lending within car dealerships (facilitated by RouteOne and Dealertrack) or split pay within e-commerce (facilitated by Klarna or Afterpay).

Successfully executing on this strategy can be hugely beneficial. Customer acquisition goes from being one of your most frustratingly large line items to a free service provided by your partners (or, in some cases, a revenue driver … BNPL providers have a negative CAC because merchants pay them to send them new customers).4

Of course there are drawback as well. Competition for embedded finance partners can be fierce and can easily lead to margin compression (ask BNPL providers). Additionally, while acquiring new customers through indirect channels can be easy and inexpensive, cross-selling additional products to them (when they have no prior connection with your brand) is extraordinarily difficult.5

Community

The argument for community, as the foundation of your differentiated distribution strategy, is essentially the opposite of the argument for convenience. Instead of financial services fading invisibly into the background, the thesis here is that interactions revolving around money can form the backbone of durable, deeply engaging communities; places where consumers will go out of their way to spend their time (and more of their money).

This argument is, ironically, the one that community banks and credit unions have been making for decades.

The key difference is in the way that ‘community’ is defined.

The digitization of financial services has led to the emergence of two new models for community-oriented distribution models — digital community banks and web3 communities.

Digital Community Banks

Neobanks like Daylight, Nerve, First Boulevard, and Panacea Financial are modernizing the concept of community banking by building banks for specific consumer segments rather than specific geographies. These segments can be defined by identity (Daylight was built for LGBTQ+ consumers, First Boulevard for African-American consumers) or profession (Nerve is a neobank for musicians, Panacea is for doctors), but they all have a few common characteristics, as Rob Curtis (CEO of Daylight) explained to me last year:

1.) The community has to self-identify as a community, for the long term. Certain groups — freelancers, students, etc. — may be bonded by common functional needs, but those bonds are temporary because these groups don’t self-identify themselves as part of a permanent community.

2.) The community has clearly identifiable and unmet product needs. If your product isn’t solving unique and meaningful pain points for the community then it’s just an affinity marketing play.

3.) The community has clearly identifiable and unmet emotional needs. It can’t just be functional. There has to be an emotional need that you can satisfy. This helps you build your brand and improve customer retention.

4.) The community has self-organizing, purpose-driven groups within it. These groups, if they value your product and connect with your brand, become an enormously important (low cost) acquisition channel.

What’s striking about this is that the product (the thing being manufactured) is a relatively small part of the equation. Much of the focus and investment is on the community aspects (how the product is distributed and engaged with), which manifests as things like this from Daylight:

we have a network of live financial coaches in the app that will help customers think about money mindset, about forming good financial habits, and improving savings rates.

If that sounds unusual for neobanks — which tend to over-invest in their product and in traditional marketing tactics like sponsoring professional sports teams and under-invest in customer service — you’re right. And that’s the point.

Web3 Communities

Let’s skip over the silly Twitter debates and just stipulate that web3, in general, can be thought of as the internet as we know it today, but with ownership more evenly distributed to creators and users, via crypto tokens.

The interesting bit of web3, for the purposes of this discussion, are the communities that can be created when creators are natively empowered to provide economic incentives and ownership to users. In this way, web3 neobanks are (if you tilt your head and squint your eyes quite a bit) like the modern version of credit unions.6

Take Eco as an example.

Eco is essentially a web3 neobank. It describes itself thusly7:

As that description suggests, Eco’s product is a combined checking, savings, and payment offering, built entirely outside of the traditional banking system.8 However, the core of the business, as CEO Andy Bromberg explains, is community (emphasis mine):

Community is at the very core of what we're trying to achieve at Eco. We can't achieve the full extent of our ambitions without the support of a community that shares our vision and wants and believes in it as much as we do, and we must reward that belief in order to sustain it.

This is where Eco (and other web3 neobanks) are different — they can programmatically reward users for their engagement with and contributions to the community via crypto tokens.

Eco calls them Eco Points, which they describe as an “open rewards currency”. It’s not abundantly clear to me how one earns Eco Points. At the moment, the primary point of engagement around Eco Points appears to be an automated Twitter account (The Accountant9) that allows Eco customers to grant Eco Points to each other for (among other things) spreading the gospel of Eco:

The specifics matter less at this point than the broader implications of this experiment (and others like it) in programmatic financial incentives for community building.

And the implications are fascinating.

Optimistically, one could envision a world in which web3 neobanks use tokenomics to generate early momentum with users and that momentum carries over into the formation of a durable community.

As an example, NFT marketplace LooksRare recently sent the biggest customers of Opensea (the biggest NFT marketplace and LooksRare’s main competitor) some of its tokens (LOOKS) and gave users the ability to earn more LOOKS tokens if they bought and sold NFTs through their platform. And what do you know? After doing this, LooksRare jumped past OpenSea in terms of total transaction value traded on its platform. Cool!

Pessimistically, one could envision a world in which web3 neobanks use tokenomics to artificially juice their growth and retention numbers while making rich people even richer and exposing ordinary customers (whose “deposits” likely won’t be FDIC insured) to an excessive number of scams. Unfortunately, LooksRare also appears to be a good example for this worst-case scenario:

In reality, this is what appears to have happened:

1. LooksRare builds an NFT marketplace with slightly lower fees than OpenSea (based on a preliminary TechCrunch analysis of their pricing schemes and media coverage).

2. LooksRare also creates a token, given to users for trading on its platform, providing a stake in its future governance in exchange for using its service.

3. Users execute wash trades of expensive NFTs to accrete LOOKS tokens, artificially boosting LooksRare volumes and putting huge amounts of LOOKS tokens into the hands of the already crypto-wealthy, ensuring that the future LooksRare DAO will be heavily influenced by a handful of users.

Convenience or Community?

This isn’t merely a choice over distribution strategy — though it is that and it will be an enormously consequential choice for founders building today — it’s also a question about what the role of financial services should be and will be in the lives of consumers.

I can’t wait to see how fintech companies answer it.

Sponsored Content

Get your Fintech Meetup ticket before prices go up this Friday! Join 1,000+ organizations already signed up for the world’s largest fintech meetings event.

Don’t miss out on the easiest way to meet leading Fintechs like Alloy, Checkout.com, NIUM, Socure & Upstart, Investors like Bain Capital Ventures, General Atlantic & Tribeca Venture Partners, Major Banks like Bank of America, Citibank, J.P. Morgan & Wells Fargo, Neobanks, 100+ Community & Regional Banks, 150+ Credit Unions, Networks, Payments Cos and many others! Virtual, March 22-24. Get Ticket Now

Short Takes

Stop trying to make ‘super app’ happen.

Walmart’s fintech startup, Hazel, is acquiring neobank ONE and early wage access provider Even, in a bid to create a “financial services super app, a single place for consumers to manage their money.”

Short take: The term ‘super app’ is constantly misused and needs to go away. A super app, by definition, is broader than just financial services. And “a single place for consumers to manage their money” already exists. It’s called a bank account. That’s what this is (and the reason to be legitimately excited about these acquisitions) — Walmart is building a digital bank for low income Americans. That’s cool! That’s the headline!

The end of an era.

UBS is acquiring robo-advisor Wealthfront for $1.4 billion.

Short take: It’s hard not to look at this as the end of the robo-advising era. The business model has just never made a lot of sense. A 0.25% fee requires massive scale to produce positive cashflow and even when you achieve that level of scale (as Wealthfront and Betterment have) you’re always living right on the edge. After failing to find traction with its pivot to self-driving money, it’s not surprising to me that Wealthfront ended up here. It’ll be interesting to see what happens to Betterment.

Where do credit reports come from?

Experian will begin allowing credit invisible consumers to create credit reports from scratch and populate them with their recurring, nondebt bill payment history.

Short take: This is the logical next step in the journey that Experian started taking with Boost. If you can add recurring, nondebt bill payments to your credit report to boost your score, why can’t you use that same data to create your credit report from scratch? I do wonder what the end of this journey looks like, particularly if regulators get involved. Why shouldn’t all credit reports require consumer permission before they are created?

Research Corner

🚨New research alert🚨

If you liked this newsletter (particularly the bit about embedded lending) then you’ll love this new research report from Cornerstone Advisors (commissioned by Newgen): Cultivating a Digital Lending Ecosystem Strategy.

The report provides a cogent definition of the term “ecosystem”, walks through the past, present, and future of digital lending ecosystems, and outlines the concrete steps that banks and fintech companies can take to build and/or participate in such ecosystems.

You can download the report, for free, here.

Alex Johnson is a Director of Fintech Research at Cornerstone Advisors, where he publishes commissioned research reports on fintech trends and advises both established and startup financial technology companies.

Twitter: @AlexH_Johnson

LinkedIn: Linkedin.com/in/alexhjohnson/

Here at Fintech Takes, we call this the AWS model — building infrastructure that is so obviously beneficial that people freak out if you even suggest that they not use it exclusively.

One of my first jobs was managing SEO for a B2B software company, so I can say with confidence that 95% of people whose answer to the question How are you going to grow? is SEO don’t have any clue what they’re talking about.

This obsessive focus on streamlining the account opening process continues to grip bank executives’ brains, as my colleague Ron Shevlin recently noted.

For more on this, read Alex Rampell’s piece on B2B2C business models.

The success rate for cross-sell off of indirect auto loan relationships is pathetically low, despite decades of effort from banks.

Credit union executives will be aghast at this comparison and I get it. Saying that web3 is like the Wild West is disrespectful to the hardworking sheriffs and posses that imposed at least a little order on those communities. Web3 is complete chaos right now, especially when compared to the carefully regulated environment that credit unions operate in. The point of the comparison is about ownership.

Etymology nerd trivia: the word “thusly” is thought to have been coined by humorist writers in the 1800s to make fun of uneducated persons who were trying to sound genteel. I’m not sure if this is a self-own.

I’ll probably dive into Eco in more depth at some point down the road, but please read Jason Mikula’s recent take on Eco if you haven’t already.

Crypto companies continue to be the best at naming things.